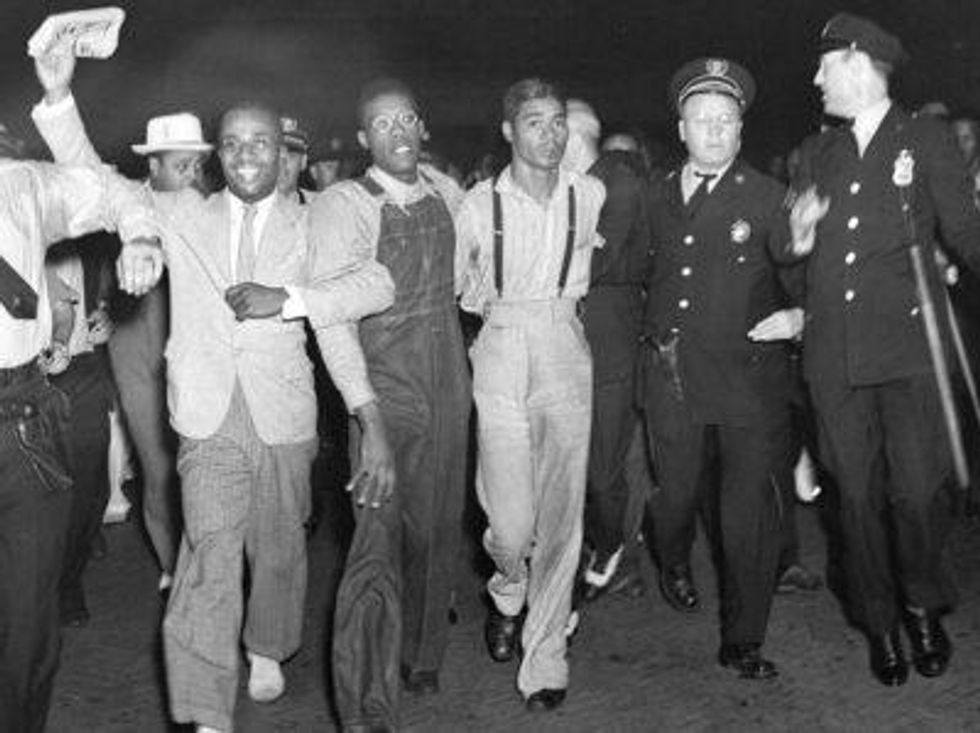

In this July 26, 1937 file photo, police escort two of the five recently freed "Scottsboro Boys," Olen Montgomery, wearing glasses, third left, and Eugene Williams, wearing suspenders, fourth left, through the crowd greeting them upon their arrival at Penn Station in New York.(Credit: AP Photo/File)

To join our Systemic Equality agenda to take action on racial justice,

click here.

After World War I, it quickly became clear that the war to make the world “safe for democracy" had not made America safe for equality. Anti-Black race riots ripped through Chicago, New York, Washington D.C., and even Elaine, Arkansas. In October 1919, after Black sharecroppers in Elaine convened a union meeting, newspapers labeled the effort a “Negro uprising." The state mobilized troops and mobs to quell the rebellion. The result was “possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in the history of the United States," concluded the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture.

The American Civil Liberties Union's origin story is tied inextricably to the xenophobic Palmer Raids, but the lesser-known events in Elaine, Arkansas were also formative. Racial violence was an unavoidable issue for any organization dedicated to the rights and liberties of everyone. Ten years earlier, the NAACP had been established to advance justice in the wake of the Springfield, Illinois race riot. During its first summer, the ACLU denounced the lynching of three Black men in Duluth, Minnesota who had allegedly raped a 17-year-old white girl. ACLU co-director Albert DeSilver wrote to Minnesota's governor volunteering assistance in “the preservation of civil liberty."

Weeks later, Minnesota Gov. Joseph A. A. Burnquist informed DeSilver that several men had been arrested in connection with the lynching. He did not tell DeSilver that none was convicted of anything serious.

Investigators realized, almost immediately, that the girl had not been raped. Nonetheless, the state tried seven Black men accused of participating in the fabricated crime. One was convicted and sentenced to hard time. That perversion of justice was not corrected until a century later when Minnesota granted the innocent man the first posthumous pardon in the state's history.

Much of the ACLU's early race-related work was similarly futile: highlighting racial atrocities America refused to stop. In 1921, the ACLU published three provocative pamphlets. The most innovative was “Debt-Slavery" by William Pickens, a sociologist and field secretary for the NAACP. Pickens argued that America had replaced chattel slavery with economic bondage and employed lynching as a form of enforcement. He saw the Elaine massacre as a defense of the “debt slave system."

The second pamphlet focused on the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan. The third, “The Fight for Free Speech," warned that reactionary forces were ascendant and observed that Negroes, foreign-born groups, and tenant farmers were “conscious of the condition but incapable of outspoken resistance."

Back then, the ACLU supported racial justice but was not at the forefront of the fight, generally deferring to the NAACP. But it assiduously documented anti-Black violence and states' restrictions on “Negroes' rights." In 1929, founding executive director Roger Baldwin suggested a radical expansion of the ACLU's role, proposing that the organization work more vigorously on behalf of “Negroes in their fight for civil rights." Additionally, Baldwin established a seat on the board for the NAACP recognizing the special relationship with the organization on civil rights cases and invited James Weldon Johnson to serve at the founding of the ACLU.

Documenting Discrimination

NAACP Secretary Walter White.

(Credit: Library of Congress)

In 1931, the ACLU issued " Black Justice," a groundbreaking study on discrimination. The report slammed laws and policies that forced Black people to attend segregated schools, barred their admission to "white" hospitals, and denied Black people a fair wage, trial by their peers, the right to vote, or the right to marry outside the race.

NAACP executive secretary Walter White called the publication "excellent publicity" for the NAACP's work. Baldwin also provided direct financial support to the NAACP through a foundation set up by Charles Garland, a young Harvard dropout who inherited a fortune he pledged to spend for "the benefit of poor as much as rich, of Black as much as white." Baldwin served as the foundation's secretary and its grants largely reflected his priorities.

In 1931, the ACLU took on the Scottsboro Boys case, which centered on nine Black youths charged with raping two white women on a freight train in Alabama. The suspects, after being pulled from the train, were rushed to trial in less than two weeks. The first two convictions came on the second day of trial. Two days later, eight of the nine stood convicted and sentenced to death. Jurors deadlocked on the fate of the ninth defendant, who was only 14.

The ACLU dispatched Hollace Ransdell, a Columbia-educated journalist, to investigate. Ransdell produced a detailed and influential report that made it clear the two women had made up the sexual assault story.

The boys' lawyers appealed to the state supreme court, which refused to overturn all but one conviction. Meanwhile, the NAACP and the Communist-backed International Labor Defense fought over which entity would represent the boys. Eventually, the lawyers came together and appealed to the Supreme Court, with longtime ACLU attorney Walter Pollak arguing the case. The court sided with Pollak, agreeing that the state, in denying the defendants their choice of counsel, had violated their right to due process.

Alabama shrugged off that and every other reversal, including two more landmark Supreme Court decisions that overturned the convictions because of the exclusion of Black jurors. Finally, in 1937, the Alabama prosecutor exonerated three of the defendants, releasing two others because they were juveniles at the time of the alleged crime. The others eventually found their way out of prison, their lives shattered because Alabama refused to admit that whites had lied about Blacks.

A Convening of Allies

In this July 26, 1937 file photo, police escort two of the five recently freed "Scottsboro Boys," Olen Montgomery, wearing glasses, third left, and Eugene Williams, wearing suspenders, fourth left, through the crowd greeting them upon their arrival at Penn Station in New York.

(Credit: AP Photo/File)

World War II provided yet another occasion for America, and the ACLU, to reflect on racial prejudice. The ACLU's major wartime anti-racism effort was the Committee on Racial Discrimination in the War Effort. Convened in early 1942, the committee was chaired by author Pearl Buck, who envisioned involving "all existing white or mostly white organizations" in a movement that would end discrimination not just in government, but in housing, wages, trade unions, and throughout society.

Winifred Raushenbush, a freelance writer hired as executive secretary, authored a widely praised pamphlet titled How to Prevent a Race Riot in Your Home Town. In "every war period the danger of race riots in great," observed Raushenbush, who suggested that with a little planning, foresight, and good will, riots could be avoided.

The committee never achieved Buck's ambitious goals, but it garnered a lot of attention. And it brought together some 30-plus organizations — including Alpha Kappa Alpha, the American Jewish Committee, the YWCA, and the National Lawyers Guild — to ruminate on race.

Japanese Incarceration and Internal Disagreement

Japanese-Americans transferring from train to bus at Lone Pine, California, bound for war relocation authority center at Manzanar, April, 1942.

(credit: Library of Congress)

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, America's military classified Japanese Americans as a security threat. Under an executive order signed by President Roosevelt, some 115,000 Japanese American residents (most of whom were U.S. citizens) were targeted for relocation from a designated exclusion zone along the West Coast.

Baldwin wrote a public letter to the president addressing the "unprecedented" order that authorized the exclusion zone, calling it "open to grave question on the constitutional grounds of depriving American citizens of their liberty and use of their property without due process of law." But the organization's board was split on the order, with a large segment of Roosevelt loyalists reluctant to criticize the war effort. The organization ultimately adopted a resolution acknowledging the government's constitutional right "to remove persons … when their presence may endanger national security."

That resolution left the ACLU's lawyers in a bind, as it was difficult to argue the internment policy was legally wrong but also constitutionally permitted. Despite the legal handcuffs it had manufactured for itself, and following internal debate, the ACLU ultimately mounted a series of challenges to Japanese internment. On June 21, 1943, the Supreme Court decided in Hirabayashi v. United States that the evacuation order was legal. That same day the court also decided in Minoru Yasui v. United States that the military-imposed curfew was a legitimate response to the harms threatened by the war.

Two other cases were not decided until after the War Department had concluded that internment was no longer a military necessity. In December 1944, the Supreme Court decided the government had no right to detain loyal citizens. It also found that ACLU client Fred Korematsu, in defying the exclusion order, had broken the law. It wasn't until the 1980s that Korematsu's conviction was vacated, and President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, issuing a formal government apology and granting monetary reparations to surviving Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

Seeking Justice in the South

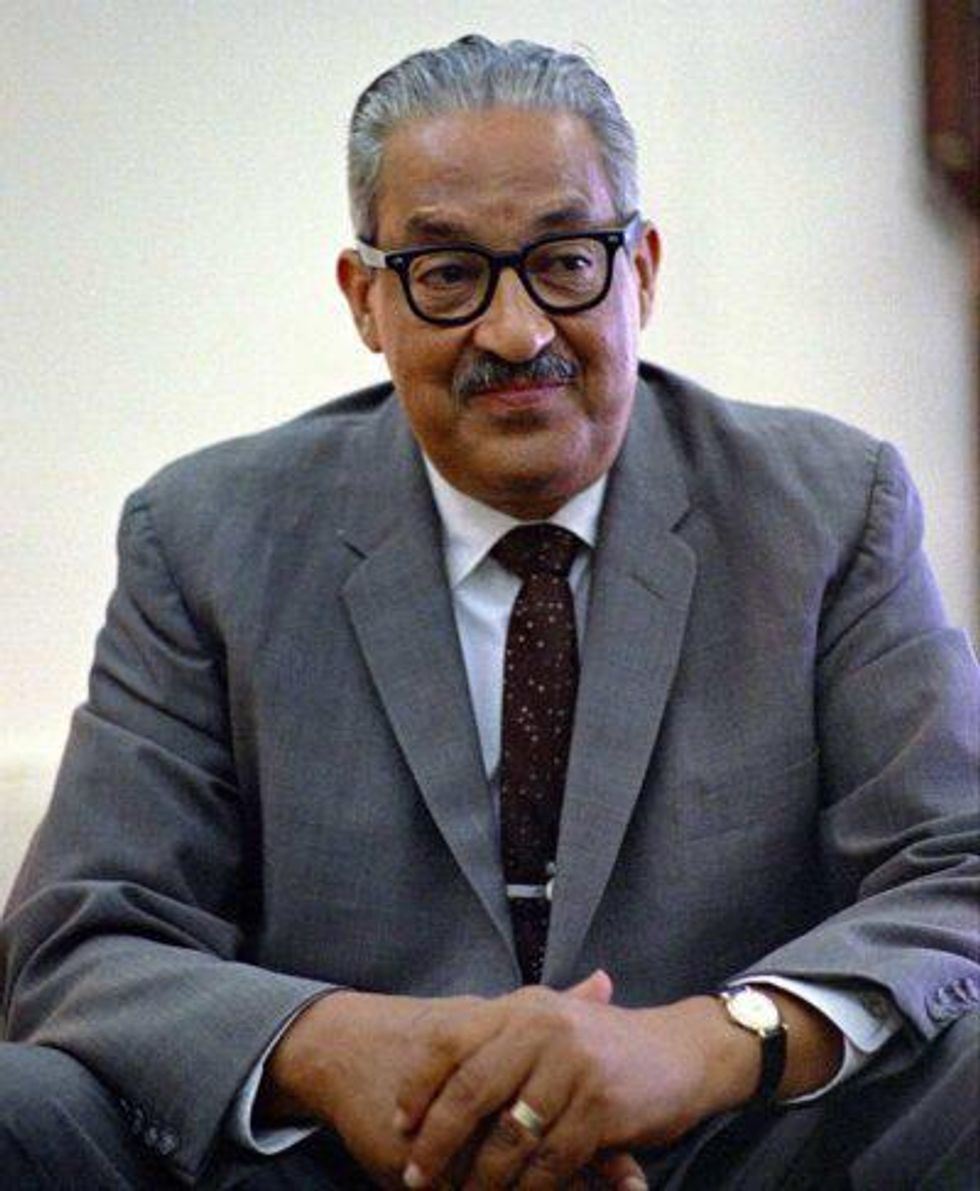

Thurgood Marshall, seen here in the White House in June 1967, the year he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

(Yoichi Okamoto/National Archives and Records Administration)

In September 1963, four Black girls were killed while attending church in Alabama when a bomb planted by the Ku Klux Klan exploded. The following morning, local lawyer Charles Morgan delivered a fiery speech that attracted national attention: "Every person in this community who has in any way contributed during the past several years to the popularity of hatred is at least as guilty, or more so, than the demented fool who threw that bomb."

Two decades earlier, in 1940, Thurgood Marshall created the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Marshall, who served on the ACLU's board from 1938 to 1946, was the architect of a brilliant legal strategy to dismantle segregation. The ACLU submitted amicus briefs for some of the LDF cases during this period including Brown v. Board of Education. By 1964, the ACLU approved a new regional office in Atlanta charged with overseeing the growing array of initiatives attacking racial oppression in the South. Morgan was named director.

Working in partnership with other civil rights organizations, the office became deeply involved in virtually every major civil rights issue in the South: expanding voting rights; ending the exclusion of Black jurors; and eliminating racially motivated sentencing disparities. The ACLU also fought prohibitions against interracial marriage, which the Supreme Court struck down in 1967 in the landmark case, Loving v. Virginia.

As the ACLU plunged into these civil rights battles, it also pushed the Warren court into rethinking criminal justice, advocating for reforms that reverberate today. That process began with the case of Clarence Earl Gideon, a drifter charged with burgling a pool hall in Florida who the Supreme Court decided was entitled to representation at public expense. Although the ACLU was not directly involved in that case, it was a driving force in those that followed. Escobedo v. Illinois (1964) revolved around Danny Escobedo, who was suspected of killing his brother-in-law. Escobedo was not informed he had a right to retain a lawyer or to remain silent, and made incriminating statements that led to his conviction. The ACLU argued his case before the Supreme Court, which concluded that Escobedo's rights had been violated.

Gideon was the prelude to Miranda v. Arizona, in 1966. Ernesto Miranda was accused of kidnapping and raping an 18-year-old woman; he confessed without being informed of his right to remain silent. The ACLU argued that Miranda's treatment violated his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The Supreme Court agreed, and Miranda rights were born.

At the time, those cases were not considered part of a racial justice agenda, but as the racial inequities in America's criminal justice system became clearer, the ACLU came to view its criminal justice work in a new light.

Ira Glasser (at left in beige suit) marching in Atlanta, GA, with Coretta Scott King (center) and others in 1997 Martin Luther King, Jr. Day parade.

(Credit: photographer unknown, Studio III: 1021 Northside Drive, Atlanta, GA 30318; 404-875-0161)

Ira Glasser believes the ACLU's deepening involvement in racial issues was inevitable. Glasser joined the New York Civil Liberties Union in 1967 and became its director in 1970. Eight years later he succeeded Aryeh Neier as executive director of the national ACLU, and quickly found himself immersed in issues of race. The Voting Rights Act, signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965 to combat discrimination against Black voters in the South, was scheduled to expire in 1982. President Reagan opposed its extension. The ACLU became a leader in the fight to preserve the law, eventually winning passage of a new bill which Reagan signed.

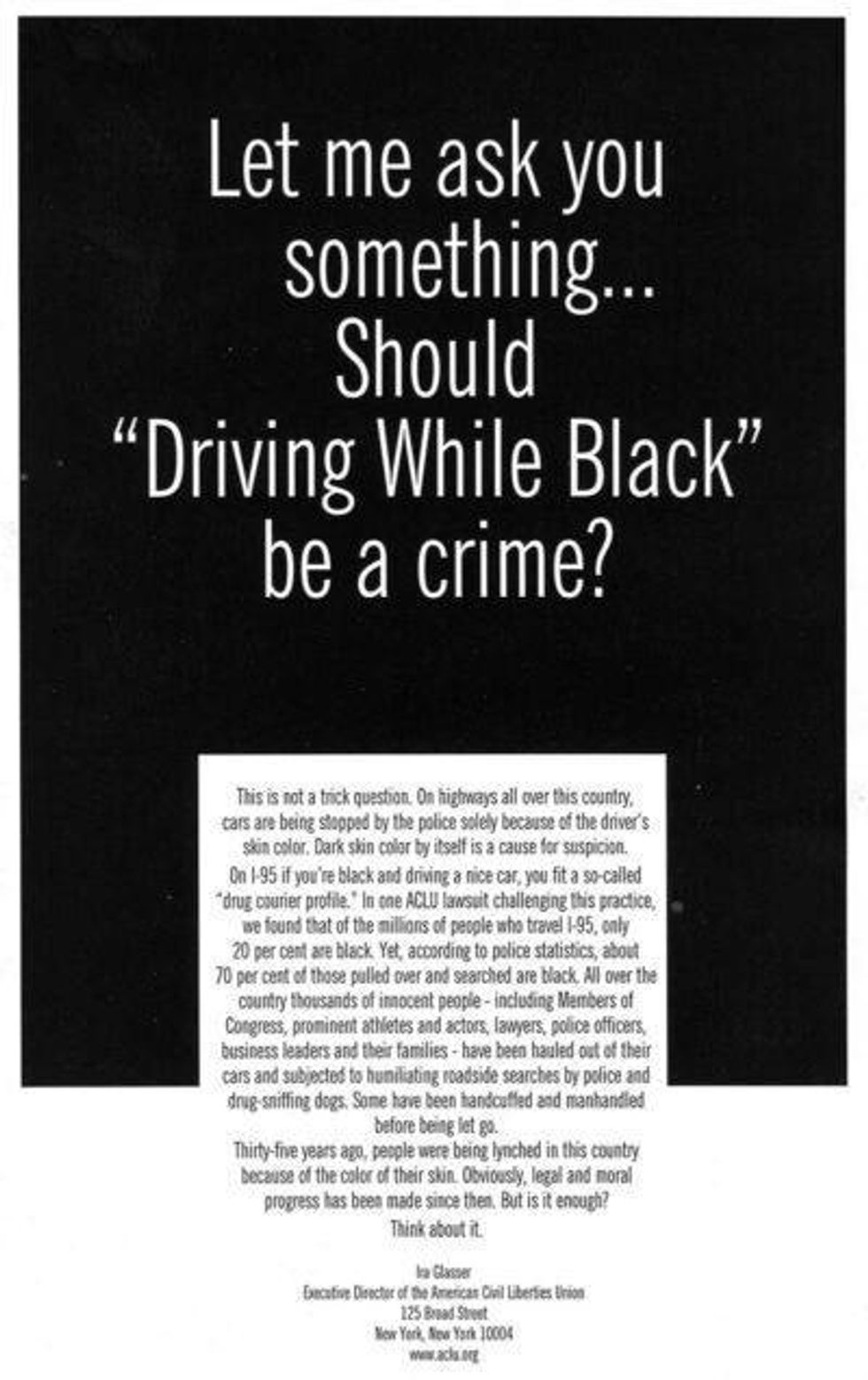

As Glasser reflected on the ACLU's myriad issues, he "began to see who was affected by these violations of civil liberties and this explosive growth of incarceration, and who was arrested, and who was prosecuted, and who was searched … They were all Brown and Black." Glasser came to see the Nixon administration's drug war as "a successor system to slavery, continuing and expanding skin color subjugation."

Those insights helped to broaden the organization's racial justice agenda, leading to an increased focus on issues such as racial profiling and stop and frisk. In the late 1990's, Michelle Alexander, who was at the time Director of the Racial Justice Project at the ACLU of Northern California, instigated a national campaign titled "Driving While Black or Brown" which revealed discriminatory policing practices and led to the introduction of legislation in 44 states to stop them.

Civil Liberties Are Civil Rights

In 2006, the ACLU formalized its investment in the fight against racial inequality by creating a national Racial Justice Program. Anthony Romero, a Puerto Rican native of the Bronx and the ACLU's first executive director of color, believed, like Glasser, that race was inextricably intertwined with other ACLU concerns. Dennis Parker, a Harvard Law graduate who had worked for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, became the program's first director. Parker noted that race was woven throughout the organization's many issue areas: "Race really informs … every area that the ACLU works [in]: women's rights, disability, or voting."

Parker knew working for the ACLU would be different from working for an organization with racial justice as its paramount mission: "At LDF … we were advocating on behalf of Black people. There may have been questions about what would be best … but it was not a question of should we be representing the Klan."

Parker's observation touched on a reality that has bedeviled the ACLU from the beginning: the occasional friction between its commitment to racial justice and also to free expression. The issue was vexing enough in the 1930's that the ACLU released a pamphlet titled "Shall We Defend Free Speech for Nazis in America?" The organization concluded that the best defense of one group's right to speak was a defense of all groups' rights.

When the ACLU was attacked in 1978 for defending Nazis intent on marching on Skokie, a Chicago suburb that housed Holocaust survivors, the answer was much the same. David Goldberger, the young Jewish lawyer leading the case, pointed out that policies Skokie employed against Nazis could also be used against Jewish war veterans. The power to shut down speech, Goldberger argued, was too important to be left to local officials: "Think of such power in the hands of a racist sheriff."

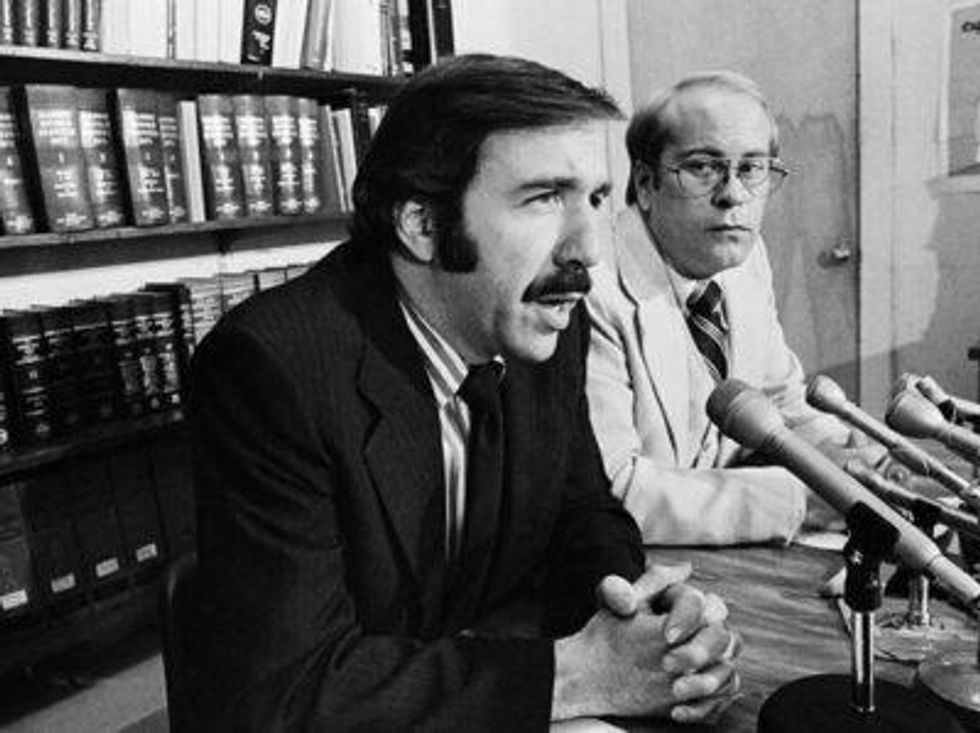

ACLU legal director David Goldberger, left, appears at a Chicago Press conference with ACLU Executive Director David M. Hamlin. Both men were happy with the court's decision to allow Frank Collin and his Nazi group to hold a rally in Chicago's Marquette Park.

(AP)

That view became so entrenched that in 2017, the ACLU represented a white supremacist group determined to hold a rally in Charlottesville. After the event resulted in a young woman's death, friends of the ACLU second guessed the organization's decision, and rigorous internal conversations about the choice to defend racists took place. The conversations resulted in case selection guidelines to assist ACLU staff in weighing the competing interests that may arise when work to protect speech may raise tensions with racial justice, reproductive freedom, or where the content of the speech conflicts with ACLU policies on those matters. The guidelines also suggest that the ACLU will generally not defend armed protest because of the chilling effect it can have on free speech.

In the ACLU's 1920 birth announcement, the new organization swore to fight "all attempts to violate the right of free speech, free press, and peaceful assemblage." That position was essentially unchanged when Roger Baldwin proposed his grand expansion. Baldwin did not foresee the possibility of that position conflicting with the defense of racial justice. Indeed, in an exchange with his biographer Peggy Lamson, Baldwin expressed frustration with Black ACLU board members who did not share his view.

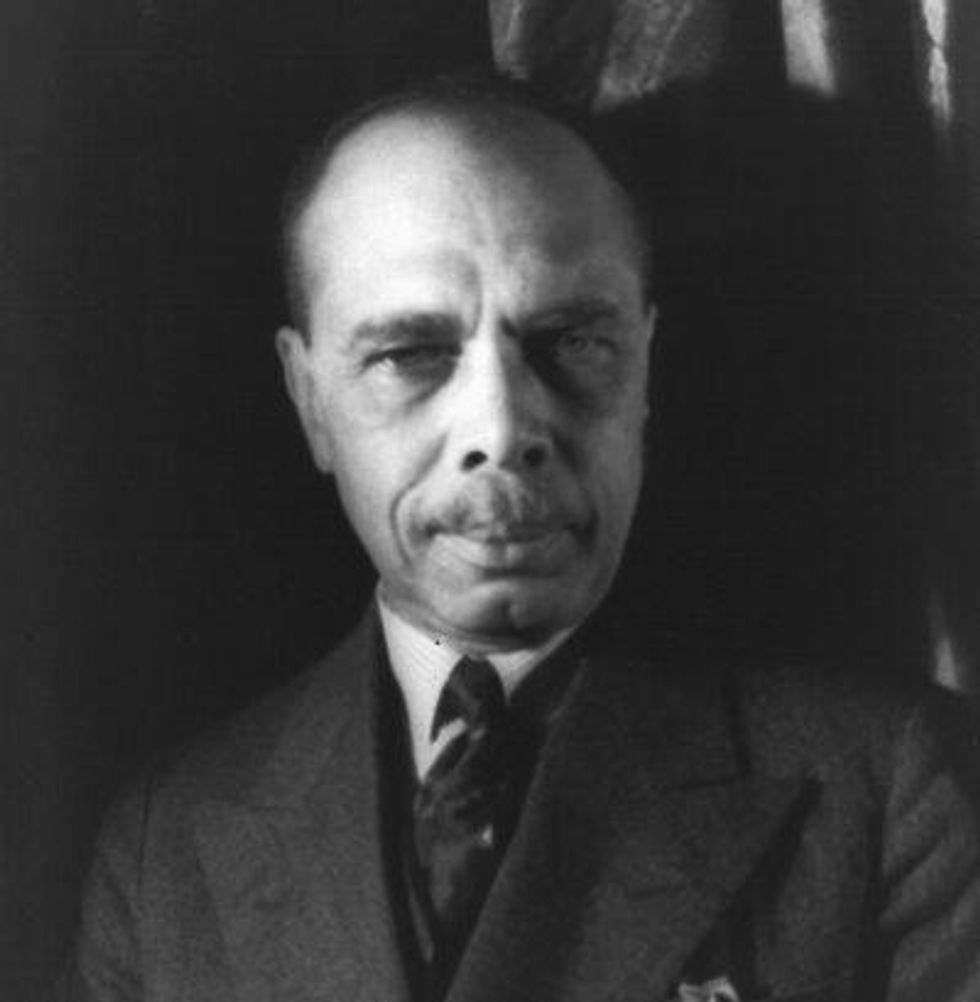

ACLU Board member James Weldon Johnson, seen here in 1932.

Credit: ACLU

James Weldon Johnson, in Baldwin's view, "couldn't see much beyond the use of civil liberties for the equality of Blacks." As Baldwin saw it, Black board members' commitment to racial equality blinded them to the larger picture. What the larger picture is, of course, depends on one's perspective.

As eager as Baldwin was to expand the ACLU's involvement in issues of race, he never saw that as the ACLU's main battle, though it was still listed among the organization's top priorities in its first annual report in 1920. He saw no need to balance the demands of racial justice with those of free speech. The modern ACLU has a more complicated view.

As Romero put it, "If I were the head of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense Fund, I wouldn't bring a Nazi case. If I were the head of the First Amendment Center, I would bring every Nazi case and not worry about the racial justice implications. I think part of what is magical and different and kind of vexing is an organization that's trying to accomplish both and say, 'They're both equally important to us.'"

That perspective suggests that an organization seriously devoted to both free speech and racial justice is obligated to tackle a question with no obvious answer: In a world where unrestrained speech is routinely weaponized to frustrate justice, what combination of rights, restraints and responsibilities moves the nation toward the most moral version of itself? The ACLU has come to see that civil rights and civil liberties are inextricable, and the protection of the latter is inherently tied to the long fight for racial justice.

What you can do:

Take the pledge: Systemic Equality Agenda

Sign up