The new redistricting cycle is set to begin in earnest on Aug. 12 with the release of key census data, and as they did a decade ago, Republicans are set to dominate the playing field to the detriment of both Democrats and democracy. Below we'll catalog how the redistricting process will work in all 50 states and which party—if any—is positioned to control how the next set of maps look, both at the congressional and legislative levels. We'll keep this post updated as new developments occur, so be sure to keep it bookmarked.

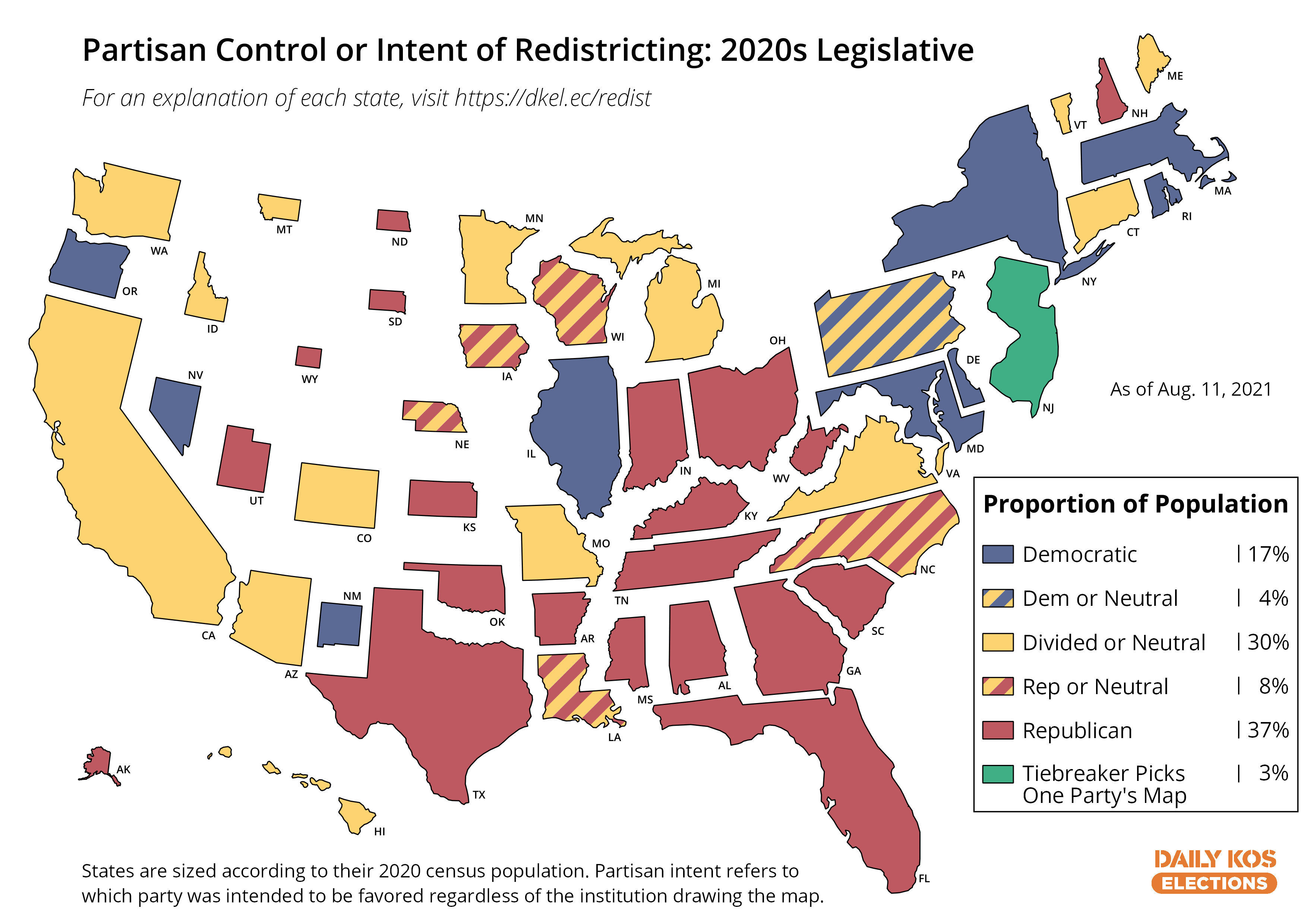

Coming out of the 2020 elections, Republicans maintained a considerable upper hand over redistricting that will let them draw four or five out of every 10 congressional districts nationally. Democrats, meanwhile, will only be able to draw fewer than two out of 10, as shown in the map at the top of this post (see here for a larger version).

This marks the third straight cycle where the GOP will enjoy a huge advantage in carving out new maps, an edge almost as extreme as the one Republicans chalked up after the lopsided 2010 elections, when they won the power to craft just over half of all House districts and Democrats just one-tenth. That huge disparity helped Republicans win the House in 2012 despite the fact that Democratic candidates won more votes that year. The same story also played out in several legislatures in key swing states multiple times over the past 10 years.

A repeat of GOP minority rule is now a strong risk for 2022 and beyond. And in an era where most House Republicans have shown their openness toward overturning Democratic victories in the Electoral College, a House where Republicans win a majority in 2024 due to gerrymandering could spark a constitutional crisis over the outcome of the next presidential election.

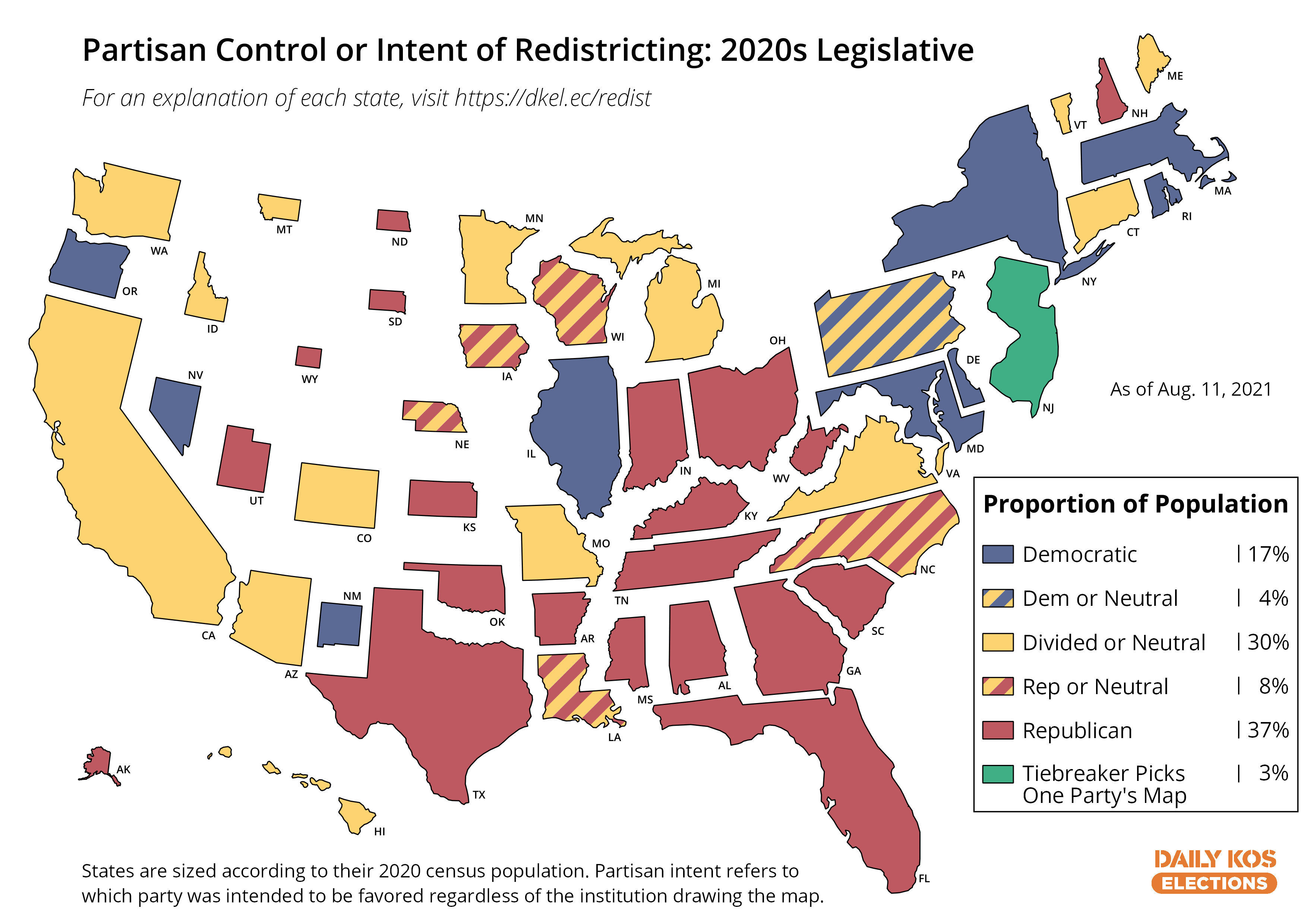

Republican minority rule is a risk in the states as well, since control of legislative redistricting will also heavily favor Republicans, as shown in the map below (see here for a larger version). This map is very similar to the one above, with the only differences showing up in Missouri, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Oregon, as well as the six states that are entitled to just a single congressional district.

The future of redistricting is also highly contingent on the Supreme Court's new far-right majority, which could both further undermine the Voting Rights Act and strip away checks on GOP state legislatures. It's possible the court could strike down all independent redistricting commissions (at least those responsible for congressional maps), or even eliminate governors' ability to veto congressional maps, under the radical argument that the Constitution gives legislatures—and legislatures alone—the power to draw new lines.

We also don't know to what degree Donald Trump's interference corrupted the accuracy of the census in ways that might have disproportionately undercounted people of color to the detriment of Democrats.

One other unexpected factor, which arose due both to the pandemic and Trump's meddling, is a delay in the release of key population data from the Census Bureau that's needed to conduct redistricting. That data, which is normally due by April 1, is now set to become available on Aug. 12, though mapmakers will have to first spend some time processing the data before they can deploy it.

That delay has wreaked havoc with redistricting timelines in many states, since a number impose legally mandated deadlines that have now become impossible to meet and may require legislation or litigation to overcome. Other states have already moved ahead with redistricting by using population estimates instead of firm census figures to draw maps sooner, which has already sparked lawsuits over the legality of using this less precise data.

Democrats in Congress still have time to systematically change these expectations by passing H.R. 1, a law that bans congressional gerrymandering nationally. However, with certain senators steadfastly opposing the elimination of the filibuster, it remains to be seen whether some sort of agreement can be reached with those holdouts to overcome GOP obstruction

While the most prominent of multiple holdouts, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, laid out the roadmap to a potential compromise in June, the prospects for H.R. 1 still seem dim. That means partisan control over the coming round of redistricting is now likely set, barring unforeseen circumstances. This means we can delve into the redistricting landscape in every state, laying out how each state's redistricting laws work and which of the two parties, if either, will call the shots. We've also addressed the threat of the Supreme Court and a tainted census in this separate article.

Below, we'll lay out the key points for understanding redistricting for each state, including:

- The number of House seats each state received in the 2020 round of reapportionment and whether a state gained or lost House seats compared to 2010

- The current partisan control over redistricting (both congressional and legislative)

- The expected partisan intent behind any final maps

- Which institutions handle the redistricting process

- What we expect to unfold

The partisan control designation looks at which party, if any, currently has power over redistricting, but partisan intent differs in that it looks at which party the responsible mapmakers sought to favor regardless of which institution draws the districts. We make this distinction because, for a variety of reasons, sometimes the two are not the same.

This happened in a few states a decade ago. For instance, even though Vermont's state government was dominated by Democrats who could have pushed through gerrymandered legislative maps favoring their own party, lawmakers actually passed largely neutral maps with widespread bipartisan support.

New Jersey, meanwhile, relies on a bipartisan commission to handle congressional redistricting, with a tiebreaking member who typically picks a map submitted by one of the parties. In 2011, that commission passed a pro-GOP gerrymander chosen by the tiebreaker, who had previously served as state attorney general under a Republican governor.

Furthermore, while we broadly describe courts as nonpartisan entities—since judges are supposed to dispassionately apply the law—they may not always be in practice when it comes to redistricting, particularly in states where they are directly elected. And even a genuinely nonpartisan court can still produce an outcome that favors one party if it doesn't seek to ensure that outcomes are fair on a partisan basis.

We will continue to add to this section as states make their way through the redistricting process over the course of 2021 and 2022; for instance, when states adopt final maps or if there are changes in the expected partisan intent, though we won't be including every minute detail given the flurry of impending activity in all the states.

● Alabama

Number of Congressional Districts: 7

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority)

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander both the congressional and legislative maps for the second decade in a row.

● Alaska

Number of Congressional Districts: 1

Partisan Control: Republican (legislative only)

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican (legislative only)

Responsible Institution(s): Politician-appointed commission of five members, with the governor picking two commissioners and the state Supreme Court chief justice, state Senate leader, and state House leader each picking one

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the legislative maps because they have a 3-2 majority on the commission. Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy and the Republican leader of the Senate collectively selected three Republican members, while the chief justice (who was appointed by a prior Republican governor but has a reputation as an independent) and the speaker of the House (a Democratic-aligned independent) both tapped independents.

● Arizona

Number of Congressional Districts: 9

Partisan Control: Nonpartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral or possibly Republican

Responsible Institution(s): Independent redistricting commission, created by voters in a 2000 constitutional amendment, with two Democrats, two Republicans, and one unaffiliated commissioner. The state commission on appellate court appointments nominates pools of 10 Democrats, 10 Republicans, and five independents, from which the four leaders of the majority and minority party in each chamber of the legislature each choose one commissioner. Those four commissioners then choose an unaffiliated tiebreaker. Maps are required to adhere to nonpartisan criteria and prioritize political competitiveness.

Current Outlook: The commission may draw either relatively nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps or ones that somewhat favor Republicans.

However, there's a significant risk that the Supreme Court will strike down all congressional redistricting commissions that were passed by citizen-initiated ballot measures without the support of legislators, including Arizona's. Republicans control the governorship and legislature, meaning an invalidated commission would also see the GOP gain full control over congressional redistricting (legislative redistricting would likely be unaffected).

Even if the Supreme Court leaves the commission in place, Republican Gov. Doug Ducey stacked the judicial nominating commission, which screens redistricting commission applicants, by appointing only Republicans and conservative-aligned independents and no Democrats.

That has raised questions about the pool of five independents from which the four partisan redistricting commissioners were able to choose a tiebreaker. While that fifth commissioner, psychologist Erika Schupak Neuberg, was selected unanimously, she has sparked concerns after twice voting with the GOP commissioners to offer key hires to firms or individuals with ties to Republicans.

It remains to be seen whether Ducey's efforts to limit the applicant pool have succeeded in securing a tiebreaking member who will ultimately side with the GOP to allow them to pass some degree of gerrymandered maps, or whether concerns over the validity of Neuberg's independence will prove unfounded.

● Arkansas

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority)

Legislative: commission created by a 1936 constitutional amendment and consisting of the governor, secretary of state, and attorney general

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander both the congressional and legislative maps.

● California

Number of Congressional Districts: 52 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Nonpartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Independent redistricting commission, created by voters in a pair of constitutional amendments passed in 2008 and 2010, with five Democrats, five Republicans, and four unaffiliated members. A panel of three state auditors chooses from applicants to select 20 Democrats, 20 Republicans, and 20 unaffiliated nominees. The four legislative majority and minority party leaders can each eliminate two applicants from each of the three pools, leaving the pools with 12 nominees apiece. From those 36, three Democrats, three Republicans, and two unaffiliated commissioners are randomly chosen, and those eight commissioners collectively select the other six.

Majority support from each of the three political groupings is required to pass a map. Maps must adhere to nonpartisan criteria that prioritize communities of interest and the protection of minority voting rights over compactness. While maps cannot be drawn to favor or disfavor a party (or incumbent), there is no explicit requirement for partisan fairness using statistical measures. Maps are also subject to potential override by voters through a ballot referendum.

Current Outlook: The commission draws relatively nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps. However, like in Arizona, California's commission could get struck down by the Supreme Court for congressional redistricting, which would leave Democrats in control.

● Colorado

Number of Congressional Districts: 8 (+1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Nonpartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Independent redistricting commissions (one each for Congress and the legislature), approved by voters in 2018. A panel of three retired appellate judges, one from each major party and one who is unaffiliated, randomly select commissioners from a pool of applicants. The four legislative party leaders choose a pool of 10 applicants each to submit to the panel of judges for random selection. Democrats, Republicans, and independents each have four members on the commission. It takes two votes from each bloc to pass a map.

Any adopted maps have to follow several strict criteria: following federal law; preserving communities of interest (which the state constitution defines in detail); keeping cities and counties whole; maximizing compactness; maximizing the number of politically competitive districts; banning the intentional favoring or disfavoring of a party or candidate; and preventing the dilution of the electoral strength of voters belonging to a racial or ethnic minority.

Current Outlook: Colorado's new commissions pass relatively fair congressional and legislative maps.

● Connecticut

Number of Congressional Districts: 5

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature, subject to a two-thirds supermajority requirement. If the legislature deadlocks, a bipartisan "backup" commission established by a 1976 constitutional amendment draws the maps. The state legislative majority and minority party leaders appoint four Democrats and four Republicans to the backup commission, and those commissioners then choose a tiebreaking ninth member.

Current Outlook: Democrats have a two-thirds supermajority in the state Senate but lack a supermajority in the state House, meaning Democrats and Republicans in the legislature would have to reach a compromise to avoid a deadlock. If not, the backup commission would have to reach a compromise on a tiebreaking member. If they fail to do so, a court will draw maps relying on the nonpartisan criteria that courts almost always use when redistricting falls to them. After the 2010 census, the two parties compromised on legislative maps at the backup commission stage, but a deadlock led to a court drawing the congressional map.

● Delaware

Number of Congressional Districts: 1

Partisan Control: Democratic (legislative only)

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic (legislative only)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats gerrymander the state legislative maps.

● Florida

Number of Congressional Districts: 28 (+1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor for congressional redistricting

Legislative: legislature only (governor lacks veto power)

Florida voters passed two "Fair Districts" amendments to the state constitution in 2010 that attempted to ban partisan gerrymandering. The state Supreme Court used those measures to curtail the GOP's congressional and state Senate gerrymanders in 2015.

Current Outlook: At the time of the previous state Supreme Court ruling, a liberal-centrist bloc held a 5-2 majority on the bench. Hardline conservatives have since gained a majority on Florida's Supreme Court thanks to Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis' 2018 victory, and it's likely that this new conservative majority will let Republicans gerrymander again, though to what degree is uncertain.

● Georgia

Number of Congressional Districts: 14

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Hawaii

Number of Congressional Districts: 2

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Bipartisan commission, in place since a 1968 constitutional amendment, with eight members appointed by the four legislative majority and minority leaders and a ninth member chosen by the state Supreme Court if the two parties cannot agree on a tiebreaker.

Current Outlook: The commission compromises on a tiebreaker or the court appoints one, leading to relatively nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps.

● Idaho

Number of Congressional Districts: 2

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Bipartisan commission created by a 1994 constitutional amendment, consisting of three Democrats and three Republicans, with the four legislative majority and minority party leaders and the two state party chairs each picking one member.

Current Outlook: The two parties either compromise as they did after 2010, or a court draws the congressional and legislative maps in case of a deadlock.

● Illinois

Number of Congressional Districts: 17 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic (congressional); Democratic (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor. If there's a deadlock, a bipartisan backup commission in place since a 1980 constitutional amendment would draw legislative districts (a court would draw the congressional map). The commission's tiebreaker is randomly chosen between nominees from each major party, giving both parties an even chance to gerrymander the legislature should the commission come into play.

Current Outlook: Democrats already enacted new legislative gerrymanders in order to meet the June 30, 2021 deadline, though their use of population estimates has already generated two lawsuits by Republicans and Latino voting advocates in response. Democrats are likely to wait to gerrymander the congressional map until census data becomes available. Deadlocks are exceedingly unlikely.

● Indiana

Number of Congressional Districts: 9

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority). If there's a deadlock for congressional redistricting, mapmaking power would shift to a backup commission in place since at least 1969, controlled by whichever party controls two out of three of 1) the governor's office, 2) the state House, and 3) the state Senate (all three are controlled by Republicans); that commission is only statutory.

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Iowa

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Nonpartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Unclear; possibly neutral or Republican

Responsible Institution(s): By statute, Iowa's Legislative Services Agency (LSA), a nonpartisan advisory institution of civil servants, proposes congressional and legislative maps based on nonpartisan criteria, though these criteria do not include the use of partisan data to ensure fairness. The LSA works with a five-member bipartisan commission, with one member chosen by each of the four legislative majority and minority party leaders; those four commissioners then choose a fifth one. The LSA proposes plans to legislators, who may either approve or reject maps without the ability to alter them. If legislators reject the agency's proposals three times, they may draw their own maps.

Current Outlook: Iowa's nonpartisan redistricting system has operated without significant controversy every decade since it was first used following the 1980 census. However, Republicans haven't held full control of state government in a redistricting year since then, and this nonpartisan system is not mandated by the state constitution but rather is only set by statute. Republicans could therefore either reject the commission's proposed maps three times to draw their own gerrymanders, or they could even amend or repeal the statute entirely, the former of which they haven't ruled out doing.

● Kansas

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans, who hold two-thirds supermajorities in both chambers of the legislature, will likely be able to override Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly's likely vetoes. If Republicans unexpectedly fail to override a veto, a court would draw nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps.

● Kentucky

Number of Congressional Districts: 6

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority)

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Louisiana

Number of Congressional Districts: 6

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Unclear; possibly neutral or Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards vetoes new Republican gerrymanders, but it's unclear whether Democrats can sustain his veto. There are 34 Democrats and three independents (who lean left on certain issues) in the state House, along with 68 Republicans. If the GOP maintains perfect unity, it needs to peel off two or more Democrats or independents in the House to override a veto (Republicans hold a veto-proof state Senate majority), which they could do by offering defectors a safe seat. If a veto is sustained, a court would draw nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps.

● Maine

Number of Congressional Districts: 2

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor, subject to a two-thirds supermajority requirement

Current Outlook: Democrats lack two-thirds majorities in the legislature, so lawmakers will either compromise and pass relatively nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps, or a court will draw nonpartisan maps.

● Maryland

Number of Congressional Districts: 8

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor. Under the state constitution, congressional redistricting is handled as typical legislation subject to a gubernatorial veto.

For legislative redistricting, the governor proposes a map to legislators at the start of the legislative session. If legislators don't act within 45 days, the governor's map becomes law; otherwise legislators may pass their own legislative maps without the possibility of a veto.

Current Outlook: Democrats use their veto-proof majorities to circumvent Republican Gov. Larry Hogan and gerrymander both the congressional and legislative maps.

● Massachusetts

Number of Congressional Districts: 9

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats use their veto-proof majorities to circumvent Republican Gov. Charlie Baker and gerrymander both the congressional and state legislative maps.

● Michigan

Number of Congressional Districts: 13 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Nonpartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Independent redistricting commission created by a 2018 amendment to the state constitution, consisting of four Democrats, four Republicans, and five unaffiliated members.

The secretary of state solicits applications to serve on the commission, reviews them, and prepares demographically and geographically representative random samples of 30 for each major party and 40 for the unaffiliated applicants. Each of the four legislative majority and minority leaders may remove five applicants from each pool, but they are not able to select members directly. Once they make their objections, the secretary of state randomly picks from the remainder.

Michigan's commission requires that at least two commissioners from each group agree to pass any map. Any maps must meet specific criteria, including: compliance with the Voting Rights Act; geographic contiguity; preserving communities of interest; partisan fairness; not favoring or disfavoring a particular candidate or incumbent; keeping counties, cities, and townships whole; and compactness.

Current Outlook: The commission draws fair congressional and state legislative maps. Like in Arizona and California, however, Michigan's independent commission could get invalidated by the Supreme Court. That would likely lead to an impasse between Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the Republican-held legislature, meaning courts would draw nonpartisan maps

● Minnesota

Number of Congressional Districts: 8

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor.

Current Outlook: Legislators compromise or deadlock, requiring a court to draw new congressional and legislative maps, which has happened for the last five decades thanks to divided government. However, without a fairness mandate, a court-drawn map won't necessarily be fair from a partisan perspective, thanks in part to the effects of white-flight segregation in the Minneapolis metropolitan area. This past decade's court-drawn maps were not designed to reflect the state's overall partisan balance and therefore gave Republicans a sizable advantage because of Minnesota's geography, which helped Republicans narrowly win the state Senate in 2020 and 2016 despite Democrats winning more votes.

● Mississippi

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor

Legislative: Legislature only (governor lacks veto power)

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander both the congressional and legislative maps.

● Missouri

Number of Congressional Districts: 8

Partisan Control: Republican (congressional only); neutral (legislative)

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican (congressional only); likely neutral (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor

Legislative: Following a 2020 ballot measure that amended Missouri's constitution, two separate bipartisan commissions (one for state Senate and one for state House) appointed by legislative leaders with an equal number of appointees from both parties will draw the maps, with 70% support needed to pass new districts. If commissioners fail to pass new districts, the state Supreme Court would appoint a commission of six state appellate judges to draw the map.

Current Outlook: Missouri voters passed an initiative in 2018 to reform the state's longstanding bipartisan legislative redistricting commissions by requiring new maps be drawn that explicitly take partisan fairness into account, which would have helped negate the geographic penalty against Democrats exacerbated by white-flight racial segregation. However, Republicans successfully deceived voters into passing a disingenuous amendment in 2020 that guts this reform by making the fairness requirement toothless and promoting compactness instead to lock in the effects of suburban segregation.

Consequently, commissioners may have no choice but to draw legislative maps that give Republicans a significant advantage beyond their popular support on par with gerrymandered maps elsewhere. Republicans will get to gerrymander the congressional map unfettered.

● Montana

Number of Congressional Districts: 2 (+1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): A bipartisan commission created by a 1972 constitutional amendment, with one appointee each from the four legislative majority and minority party leaders, and a tiebreaker chosen by the state Supreme Court if the commissioners can't agree on one.

Current Outlook: Montana's commission draws relatively nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps.

● Nebraska

Number of Congressional Districts: 3

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Unclear; possibly neutral or Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans narrowly lack the two-thirds supermajority needed to overcome a potential filibuster by Democratic legislators. However, Republicans could eliminate the filibuster rule with a simple majority, though they have yet to show much interest in doing so.

If Republicans can overcome a filibuster, possibly by cutting a deal with an individual Democrat or two, they could gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps. However, if they can't and Democrats hold firm, either the two parties would have to compromise or a court would draw nonpartisan districts.

● Nevada

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● New Hampshire

Number of Congressional Districts: 2

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the maps for Congress, the legislature, and New Hampshire's unusual Executive Council, which has veto power over executive and judicial appointments, pardons, and large contracts.

● New Jersey

Number of Congressional Districts: 12

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic or neutral (congressional only); likely Democratic or Republican (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: A bipartisan commission created by a 1995 constitutional amendment, consisting of six Democrats, six Republicans, and a tiebreaking member

Legislative: A bipartisan commission created by a 1966 constitutional amendment, consisting of five Democrats, five Republicans, and a tiebreaker if needed

Congressional commissioners are appointed by the four legislative majority and minority party leaders and the two major-party state chairs, with a tiebreaker chosen by the state Supreme Court if the parties can't agree on one. The legislative commissioners are chosen by political party chairs, with a court-appointed tiebreaker only if needed.

Current Outlook: In past decades, the tiebreaker has effectively faced a choice of passing one party's gerrymander or the other's, although these maps weren't as extreme as they likely would have been if legislators had had free rein to draw their own lines.

After the two parties on the congressional redistricting commission couldn't decide on a tiebreaker, they each nominated a candidate for the state Supreme Court to pick from. In early August the court chose the Democratic backed nominee, former state Supreme Court Justice John Wallace. Consequently, the commission is likely to produce either a map that is favorable to Democrats or is more neutral rather than the current one that favors Republicans. The legislative commission has yet to select a tiebreaker.

Thanks to the delayed release of key census data, legislative redistricting was postponed to the 2023 election cycle, meaning the 2021 elections will be held using the 2011 map, for which the tiebreaker chose the Democrats' proposal.

● New Mexico

Number of Congressional Districts: 3

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps, though it remains to be seen if a newly adopted bipartisan commission that is advisory in nature will lessen the degree to which Democrats gerrymander.

● New York

Number of Congressional Districts: 26 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor, with input from a new bipartisan advisory commission created by a 2014 constitutional amendment, with members chosen by legislative leaders and their appointees. However, expert interpretations differ as to what threshold lawmakers would need to reach in order to pass maps on a partisan basis (rather than those proposed by the commission), since the amendment's wording is ambiguous.

In the event that one party controls both legislative chambers, the amendment requires seven of 10 commissioners, including at least one appointed by each legislative leader, to approve sending a map to the legislature. If the commissioners fail to reach a consensus, the map with the most support is instead forwarded to legislators. A two-thirds supermajority is required for the legislature to pass any commission-proposed maps when one party controls both chambers. (In the event of divided legislative control, only simple majorities are needed.)

If lawmakers reject the commission's proposals twice, they may amend them and draw their own maps. In such a case, however, it is not clear whether legislators would need a two-thirds supermajority to do so or just a simple majority. Lawmakers are also limited by statute from changing more than 2% of the population in any district proposed by the commission, though this rule could be repealed.

Current Outlook: Democrats hold two-thirds supermajorities in both chambers, as well as the governorship. They have also placed a constitutional amendment on the ballot this November that would reduce the threshold for approving or overriding the commission's maps. The amendment would require only a simple majority, regardless of partisan control of the legislature, to approve maps passed by the commission. It would also take a 60% majority to approve maps if the commission fails to pass any. It's still not clear, however, what threshold would be necessary for lawmakers to pass their own maps if the legislature rejects the commission's maps twice.

Given Democrats' interest in lowering the thresholds, it's likely they will seek to assert greater partisan control over the mapmaking process. Even if the new amendment doesn't pass, though, they will still have the necessary supermajority to override the commission even under the most maximal interpretation of what the 2014 amendment requires (i.e., two-thirds).

● North Carolina

Number of Congressional Districts: 14 (+1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Unclear; possibly Republican or neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Legislature (governor lacks veto power)

Current Outlook: Republican legislators gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps. However, it's possible the state Supreme Court (which has a Democratic majority) or a lower court will strike them down for violating the state constitution, following 2019's rulings against the GOP's 2017 legislative gerrymanders.

● North Dakota

Number of Congressional Districts: 1 at-large district

Partisan Control: Republican (legislative only)

Partisan Intent: Republican (legislative only)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor.

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the legislative maps.

● Ohio

Number of Congressional Districts: 15 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor, with a bipartisan backup commission created by legislators in a 2018 constitutional amendment, consisting of the governor, secretary of state, state auditor, and one appointee each by the four legislative majority and minority party leaders in case of legislative deadlock.

Legislative: Uses a similar commission structure, created by legislators in a 2015 constitutional amendment, without the legislature getting a vote on the maps.

Implementing maps for the whole decade requires bipartisan support, but the legislative majority party can pass a party-line congressional map that will be in effect for four years instead of 10. Whichever party holds a majority on the legislative redistricting commission can also pass a party-line map that will also be in effect for four years. (Such four-year maps can be passed repeatedly when a previous map expires, both for congressional maps and legislative maps.) Congressional criteria restrict how cities and counties can be divided and bar maps that "unduly favor" a party but don't explicitly require partisan fairness.

Current Outlook: Republicans will likely use their legislative and commission majorities to pass congressional and legislative gerrymanders that are only slightly more restrained than their current maps for four years. Alternately, they could pressure Democrats into passing 10-year maps by threatening to pass more extreme four-year gerrymanders if Democrats don't agree to somewhat more modest 10-year gerrymanders. Passing extreme gerrymanders every four years could in fact be the optimal strategy for Republicans because it would give them the chance to refine their gerrymanders every two elections instead of every five.

● Oklahoma

Number of Congressional Districts: 5

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican (congressional); Republican (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor. A backup commission created by legislators via a 2010 constitutional amendment, consisting of three Democrats and three Republicans appointed by the governor, state Senate leader, and state House leader, draws the legislative maps in case of a deadlock.

Current Outlook: Republicans have already passed new gerrymanders of the state legislature using population estimates, risking a lawsuit over the legality of using such data. Most Democrats voted for these new maps, possibly in return for individual Democrats getting favorable seats at the expense of their party overall. Republicans are also positioned to gerrymander the congressional map at a later date.

● Oregon

Number of Congressional Districts: 6 (+1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Divided state government (congressional only); Democratic (legislative)

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral (congressional); likely Democratic (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor. In the event of a deadlock, a court draws the congressional map but the secretary of state draws the legislative maps, subject to certain requirements, including that districts preserve the integrity of political jurisdictions.

Current Outlook: Legislators either compromise on the congressional map or a court draws it, but Democrats will be able to gerrymander the legislative maps. Since 2019, Oregon Republicans have repeatedly staged legislative walkouts to deny Democrats the two-thirds supermajority needed for a quorum.

Democrats struck a deal earlier this year in which they agreed to give up their majority on the state House redistricting committee and give the GOP veto power over congressional redistricting in exchange for Republicans agreeing to stop obstructing certain legislation, though Republicans still retain the ability to abuse the quorum requirement at any time. However, should Republicans block Democratic legislators from passing new legislative maps, Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan would take over the process and possibly produce maps that would favor her party.

● Pennsylvania

Number of Congressional Districts: 17 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Divided state government (congressional) and bipartisan commission (legislative)

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral (congressional); possibly Democratic or neutral (legislative)

Responsible Institution(s): Congressional: state legislature and governor

Legislative: A bipartisan commission created by a 1968 constitutional amendment handles legislative redistricting, with the legislative majority and minority party leaders each choosing one commissioner. In the event of a commission deadlock, the state Supreme Court appoints a tiebreaking fifth member.

Current Outlook: For congressional redistricting, Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf vetoes a new Republican gerrymander, and a court draws nonpartisan districts. For the legislative redistricting commission, Pennsylvania's Supreme Court, where Democrats hold a 5-2 majority, appointed former University of Pittsburgh chancellor Mark Nordenberg as tiebreaker.

However, it remains to be seen whether Nordenberg will be inclined to use the same partisan fairness criteria that the court implicitly adopted when it struck down the GOP's congressional gerrymander under the state constitution in 2018 and replaced it with a fairer map, or whether he will instead let Democrats try to gerrymander to obtain a partisan advantage as the GOP did when they controlled the court the prior two decades.

● Rhode Island

Number of Congressional Districts: 2

Partisan Control: Democratic

Partisan Intent: Likely Democratic

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● South Carolina

Number of Congressional Districts: 7

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● South Dakota

Number of Congressional Districts: 1

Partisan Control: Republican (legislative only)

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican (legislative only)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the legislative maps.

● Tennessee

Number of Congressional Districts: 9

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority)

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Texas

Number of Congressional Districts: 38 (+2 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor. In case of a deadlock for legislative redistricting only, a backup commission created by a 1948 constitutional amendment takes over. It consists of the lieutenant governor, state attorney general, comptroller, land commissioner, and state House speaker, all of whom are currently Republicans.

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Utah

Number of Congressional Districts: 4

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor, with assistance from a bipartisan advisory commission. Voters passed a 2018 ballot initiative creating the commission to minimize gerrymandering, but Republican lawmakers effectively gutted it by passing a law last year in response. The 2020 law repealed a requirement that maps must pass with the support of at least one member from the other party and weakened the nonpartisan criteria governing the drawing of such maps to eliminate a partisan fairness mandate. Republicans also weakened the ability of voters to sue in state court if legislators pass districts that violate those nonpartisan criteria.

The 2018 initiative created a commission consisting of six appointees from the four legislative majority and minority party leaders, three from each major party, and a chair appointed by the governor, giving Republicans a one-seat majority. Lawmakers can ultimately reject the commission's proposals and draw their own maps, nominally subject to nonpartisan criteria.

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps, with the commission and courts providing only modest constraints.

● Vermont

Number of Congressional Districts: 1

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: Democrats and their allies in the Progressive Party lost their collective two-thirds supermajority in the state House in 2020, which they needed to override Republican Gov. Phil Scott's vetoes and gerrymander the legislature. Left-leaning independents now hold the balance of power for veto overrides in the state House, so it's unlikely that the governing coalition will be able to pass overtly partisan gerrymanders. (Democrats have a supermajority on their own in the state Senate.)

However, given Vermont's penchant for rejecting sharp-edged partisan politics common just about everywhere else, it's possible Democrats would not even be interested in attempting to pass a gerrymanders over a Scott veto. In fact, after 2010, Democrats passed new maps with wide GOP support, so something similar may happen after 2020.

● Virginia

Number of Congressional Districts: 11

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Bipartisan commission created by a 2020 constitutional amendment, with the commission consisting of 16 members evenly divided between the two major parties. Half of the commission consists of legislators while the other half are citizen members chosen by retired judges. The commission's maps must be approved by the state legislature and governor to take effect, but lawmakers cannot amend them or draw their own. An additional statute adds nonpartisan criteria, including a ban on maps that intentionally and unfairly favor a party or candidate. If commissioners and lawmakers fail to agree on new districts, the state Supreme Court will take over and draw them.

Current Outlook: Commissioners likely either compromise and draw maps that modestly gerrymander in favor of incumbents from both parties, or deadlock and send the process to court. Some Democrats are concerned that the conservative-dominated state Supreme Court will draw stealth GOP gerrymanders if given the chance. However, the court would still be bound by the same nonpartisan criteria that commissioners are.

● Washington

Number of Congressional Districts: 10

Partisan Control: Bipartisan commission

Partisan Intent: Likely neutral

Responsible Institution(s): Bipartisan commission created by a 1982 constitutional amendment, consisting of one appointee made by each of the four legislative majority and minority party members. There is no tiebreaking member, so a deadlock would lead to a court drawing the maps. The commission submits its maps for legislative approval, and the legislature can only amend the proposals with two-thirds supermajorities. Current statute limits any amendments to altering 2% or less of a proposed district's population.

Current Outlook: Commissioners likely engage in modest bipartisan gerrymandering to protect incumbents from both parties.

● West Virginia

Number of Congressional Districts: 2 (-1 compared to 2010)

Partisan Control: Republican

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor (veto override takes a simple majority)

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the congressional and legislative maps.

● Wisconsin

Number of Congressional Districts: 8

Partisan Control: Divided state government

Partisan Intent: Unclear; possibly neutral or Republican

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor

Current Outlook: One possibility is that Democratic Gov. Tony Evers vetoes new Republican gerrymanders, and a court draws nonpartisan congressional and legislative maps. However, Republicans are reportedly planning to ask their 4-3 conservative majority on the state Supreme Court to strip Evers of his power to veto redistricting, and it's unclear whether the justices are inclined to go along with such a scheme. Republicans have additionally been maneuvering to ensure that Wisconsin's Supreme Court would be the one to draw the maps in the event of a deadlock rather than a lower state court or a federal court.

● Wyoming

Number of Congressional Districts: 1 at-large district

Partisan Control: Republican (legislative only)

Partisan Intent: Likely Republican (legislative only)

Responsible Institution(s): State legislature and governor.

Current Outlook: Republicans gerrymander the legislative maps.