John Roberts and the second coming of Dred Scott

The fix was in even before Chief Justice Roger Tane announced the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford on March 6, 1857. Of the nine Justices on the bench, seven had been appointed by pro-slavery Presidents, and five, including Taney, were either current or former slaveholders. Dred Scott, the enslaved Black man who sought his freedom before the highest tribunal in the land, never had a fighting chance.

This article originally appeared on The Progressive.

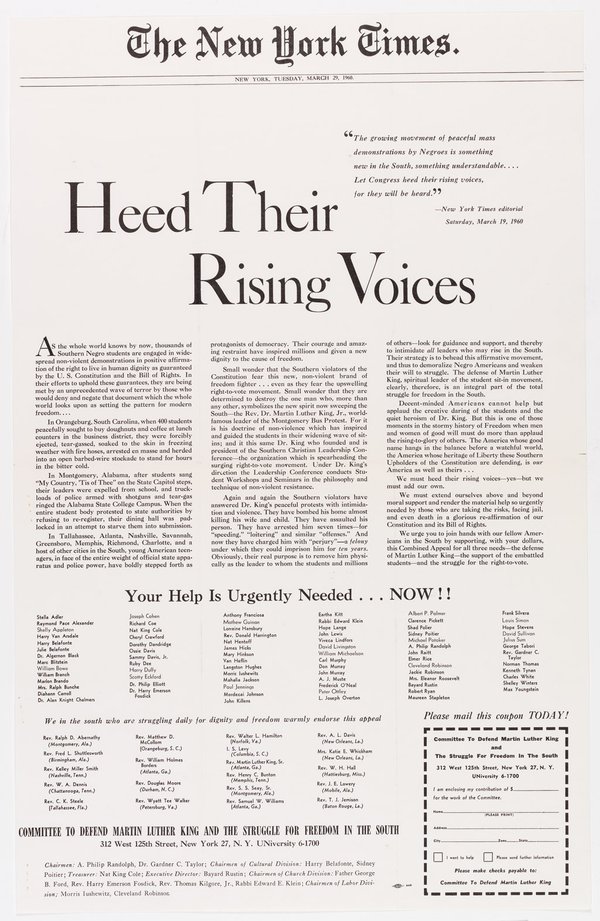

Reading in a barely audible voice before a packed audience in the Court’s old chamber at the U.S. Capitol, the frail seventy-nine-year-old Taney surprised no one when he announced the panel’s 7-2 majority opinion, proclaiming that Black people could never be citizens of the United States. Only two days earlier, the nation’s new President, James Buchanan, devoted a considerable portion of his inaugural address to the case, urging the Court to resolve the issue of slavery’s constitutionality once and for all, and imploring the nation to accept the Court’s resolution. Behind the scenes, Buchanan had been communicating directly with at least two Justices to pressure them and their colleagues to rule against Scott, and give their imprimatur to the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” that would leave slavery’s future to be determined by the states.

The pressure campaign resulted in a decision that went well beyond the boundaries of popular sovereignty. In words that have reverberated through the ages, Taney held that Black Americans, no matter where they resided, had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Dred Scott is widely regarded as the single worst ruling in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. It fractured an already divided country, set the stage for the election of 1860 as a battle between slavery and democracy, and helped precipitate the Civil War. The decision was roundly denounced in the North, undermined the Court’s legitimacy, and sparked a Constitutional crisis that was only resolved with the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

Some 167 years later, the fix was also in before Chief Justice John Roberts announced the Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity on July 1 in Trump v. United States, which may well be the Court’s worst ruling since Dred Scott.

Trump had been charged in the case with four felony counts by Justice Department Special Counsel Jack Smith for attempting to subvert the results of the 2020 election. Trump lost a motion to dismiss on grounds of immunity before District Court Judge Tanya Chutkan, and came up short on an appeal to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Desperate to avoid trial and a possible prison sentence, he turned to the Supreme Court.

At first considered a legal longshot, the immunity claim resonated with the Court’s six Republican Justices during the oral arguments held on April 25. Roberts disparaged the D.C. Circuit’s ruling that Presidents were not above the law or beyond prosecution as a mere “tautological statement.” Justice Neil Gorsuch, the first of Trump’s three appointees to the panel, declared that the case required an opinion “for the ages” that would extend beyond the specific allegations alleged against the former President. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Trump’s second appointee, criticized the history of independent counsel investigations for hampering the operations of several Presidents. Justice Samuel Alito worried that without immunity, former Presidents would become victims of partisan warfare waged by their successors.

The Court’s decision—released on July 1, the final session of the October 2023 term—rewarded Trump with an unprecedented victory. All six Republican-appointed Justices joined a majority opinion, authored by Roberts, that conferred “absolute immunity” on Presidents for exercising their “core powers” (those specifically enumerated in Article II of the Constitution, such as the pardon power), and “presumptive immunity” for all other “official acts.” Although the opinion permits prosecution for unofficial acts, Roberts offered no clear guidance on the dividing line between official and unofficial conduct. Acknowledging that the distinction between the two “can be difficult,” the closest he came to a definition is a sentence describing an unofficial act as one that is “manifestly or palpably beyond [the President’s] authority.” To complicate matters further, Roberts also held, incomprehensibly, that in determining whether an act is official or unofficial, courts “may not inquire into the President’s motives.”

All three Democratic-appointees dissented. In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor blasted the majority on both technical and substantive grounds. Attacking Roberts’s craftsmanship, she charged that “the majority’s dividing line between ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ conduct narrows the conduct considered ‘unofficial’ almost to a nullity.” She also accused Roberts and the majority of inventing “an atextual, ahistorical, and unjustifiable” concept of immunity. “The Constitution’s text contains no provision for immunity from criminal prosecution for former Presidents,” she wrote, citing the famous Watergate tapes decision of United States v. Nixon. She concluded in a sad and angry lament, “The relationship between the President and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably. In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.”

Whether the Supreme Court’s decision will completely derail the Special Counsel’s election-subversion prosecution or just severely limit it remains to be seen. The case was remanded to Judge Chutkan in early August, who has been given the Herculean task of deciding whether, and to what extent, the case can move forward. In the meantime, she has delayed the trial until after the election.

Although history, as Mark Twain is credited with saying, never exactly repeats but rhymes, there are indeed unmistakable parallels between Dred Scott and Trump v. United States. Whereas the Dred Scott bench was dominated by slaveholders, the current Supreme Court is controlled by six appointees of Republican Presidents, all of whom are either current or former members of the ultra-right Federalist Society. Like the Taney Court, the Roberts Court is on a mission to use its extraordinary judicial powers to move the country in a radical rightward direction.

And the parallels do not end there. The majority opinions in each case were written by Chief Justices who had spent their early careers as zealous political advocates. Before ascending to the Supreme Court in 1836, Taney was elected to the General Assembly of Maryland, and later served as a loyal foot soldier to President Andrew Jackson, first as Secretary of War and then as Attorney General. Taney backed Jackson in his battle to destroy the Second National Bank. And as Attorney General, he penned an advisory opinion that prefigured his Dred Scott ruling, arguing that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were inapplicable to Black people, even those living in free states.

Similarly, as a young lawyer, Roberts established himself as a dependable rightwing operative, clerking for the late Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, and continuing in his work for the Reagan and senior Bush Administrations, where he honed his skills as an ardent opponent of the Voting Rights Act. Later, as an attorney in private practice, he played an important role as a consultant, lawsuit editor, and prep coach for the GOP’s legal arguments in the run-up to Bush v. Gore, the case that decided the 2000 presidential election.

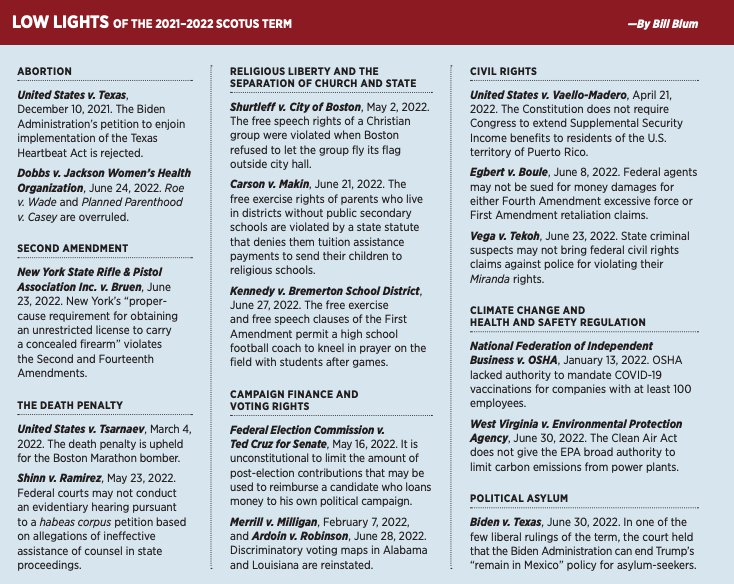

Just as Taney destroyed his reputation as a strict constructionist with Dred Scott, Roberts has forever altered his image as an institutionalist committed to promoting judicial minimalism and preserving the Court’s integrity. In fact, Roberts’s tenure as Chief Justice has been marked by an extraordinary degree of judicial activism. Most notably, he invented the theory of “equal state sovereignty” to gut the Voting Rights Act with his majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). He has also used the once-obscure “major questions” doctrine—which holds that regulatory actions that affect issues of “great social importance” are invalid unless they are precisely authorized by Congress—to strike down environmental programs and dismantle what conservatives call the “administrative state” (See sidebar: “Deconstructing the Administrative State”).

But according to historian Sean Wilentz, “Until Trump v. United States, no one decision by the Roberts Court carried significance comparable in magnitude to that of Dred Scott . . . Trump v. United States is distinct as a deliberate attack on the core institutions and principles of the republic, preparing the way for a MAGA authoritarian regime much as Dred Scott tried to do for the slavocracy.”

Wilentz also argues that the Roberts Court deployed fake history and phony originalism to come to Trump’s rescue in Trump v. Anderson. Decided on an expedited basis in March, Anderson, Wilentz writes, “brazenly gutted Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment” to permit Trump to remain on the presidential ballot in Colorado by “inventing the idea that the power to disqualify insurrectionists from office lay entirely with Congress” rather than also residing with the states, as the framers of the Amendment intended.

Wilentz further contends the Court abandoned “textualism”—the idea popular especially on the right that statutes must be read strictly according to the plain meaning of their terms—with Roberts’s majority opinion in Fischer v. United States. The Court in Fischer held that the federal statute criminalizing obstruction of Congress applies only to the destruction of documents and not to any violent acts perpetrated by the January 6 insurrectionists. Some 330 alleged insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol have been charged under the same statute, and could have their sentences reversed by this decision.

In yet another echo of Dred Scott, the Roberts Court’s decisive lurch to the right has undermined the institution’s public standing and perceived legitimacy. Recent polling reveals that only 36.5 percent of the public approve of the Court while 54.7 percent disapprove. Seven in ten Americans think the Justices are motivated more by ideology than a commitment to impartiality.

At the same time, the Roberts Court has been besieged by an embarrassing ethics crisis fueled primarily by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Both men have been accused of failing to report luxurious vacations paid for by rightwing billionaires on their federally mandated financial disclosure forms. Both men have refused to recuse themselves from cases involving the January 6 insurrection despite their spouses’ links to the insurrectionist and MAGA movements.

Alito brought additional disgrace to the Court when he was secretly recorded by a liberal filmmaker in June at a meeting of the Supreme Court Historical Society, weighing in on the nation’s ongoing culture wars, and remarking: “One side or the other is going to win. I don’t know. I mean, there can be a way of working, a way of living together peacefully, but it’s difficult, you know, because there are differences on fundamental things that really can’t be compromised.”

In response to mounting public concern, the Court adopted an ethics code for the first time in its history last November. The code, however, has been criticized as “toothless,” as it lacks any enforcement mechanism.

All this has given new purpose and energy to the call for wide-ranging Court reform. In a June op-ed for The Washington Post, President Joe Biden joined the chorus, calling for legislation to impose term limits on Supreme Court Justices, a binding code of ethics and a Constitutional amendment to override Trump v. United States, re-establishing the principle that no one—including the President—is above the law. All three proposals . Biden stopped short, however, of advocating for Court expansion, which see as the only sure way to wrest control of the Court from the radical right (see sidebar: “Fixing the Supreme Court”).

Sadly, as justice correspondent for The Nation Elie Mystal noted in a July article, “There’s no legislative fix for the problems the Court has created . . . . The conservative Justices fear nothing: not the people, not the Congress, and certainly not the Democrats. They are drunk on their own power because nobody will cut off their supply.”

Like Wilentz, Mystal asserts that the Court’s just-completed term “will have a bigger impact on the rule of law and our political future than anything the Court has done since 1857’s Dred Scott decision.” Long an advocate for getting tough on Roberts and his GOP confederates, Mystal sees expansion as the best, and perhaps the only, peaceful alternative to the other option—open defiance of the Court’s rulings, likely leading, in his estimation, to a new civil war—exactly where Dred Scott took us all those years ago.

- The Republican vote thieves strike again ›

- 'Subpoena him': Critics blast chief justice’s 'hubris' for refusing to testify before the Senate ›

- SCOTUS ethics code debate split liberal and conservative justices amid 'legitimacy crisis' - Alternet.org ›