Here are 7 crucial takeaways from Robert Mueller's testimony

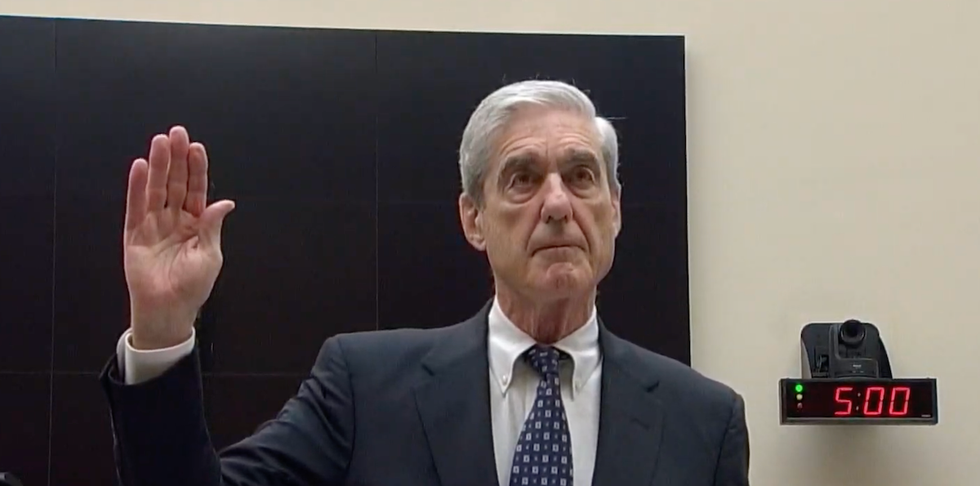

Former Special Counsel Robert Mueller's congressional testimony on Wednesday didn't make a bang, but over the course of the day, it slowly rose to a boil. And despite the fact that Mueller provided few new revelations — with at least one major exception, which I'll get to — it provided important insight into the case against President Donald Trump and state of the federal government.

Here are my seven key takeaways from the hearing:

1. Mueller was willing to contradict Trump.

When asked specifically to address Trump's claims that his report exonerated the president, Mueller didn't hesitate. He made clear that the report does not exonerate Trump, and that it did not conclude that there was "no obstruction" by the president.

Of course, anyone paying attention would have known that Trump's "no obstruction" line was a complete fabrication. But it wasn't a foregone conclusion that Mueller would be so direct — he could have tried to avoid directly contradicting the president. Having this on the record and under oath denial of Trump's claims is useful.

Mueller even went so far as to say that calling Trump's praise of WikiLeaks during the 2016 campaign "problematic" would be an "understatement." And asked about the Trump campaign's behavior toward Russia ahead of the election, Mueller said he feared it would become the "new normal."

2. Republicans are mad that Trump was investigated, but not mad about anything else.

Democrats used their time questioning Mueller to plumb the depths of the details in his report. Republicans, on the other hand, fumed and frequently lashed out at Mueller, floating common right-wing conspiracy theories and pressing him on various issues he said he could not or would not address. They also attacked the integrity of Mueller's team and his legal reasoning.

They showed little interest, though, in the Russian criminal conspiracies Mueller uncovered that targeted the 2016 election (One welcome exception to this pattern was Rep. Will Hurd of Texas). They were even less concerned with the Trump campaign's ties to Russia or the president's apparent efforts to obstruct justice.

3. Mueller's own sense of "fairness" really hurt his case.

In one particular area, Republican criticism of Mueller did gain some traction. Multiple GOP lawmakers argued that Mueller didn't complete his job as special counsel because he didn't offer a prosecution or declination decision about Trump's conduct. Instead, he laid out the evidence and analysis of Trump's conduct, saying it may be left in the hands of a future prosector or Congress. Some argued that this move was unfair to Trump because prosecutors aren't supposed to compile evidence against someone they're not planning on charging.

Mueller's response to this argument is that because Justice Department policy forbids indicting a president — but allows investigating him or her — he was in a unique position. Therefore, it seems, the usual prosecutorial rules don't necessarily apply. Also, inconveniently for Republicans, it was the attorney general who made the report public, not Mueller.

But I think the Republicans' argument is actually the stronger of the two sides. Mueller had two options that would have served him and the country much better than the decision he made. He could have written a nearly identical report with one minor change: Instead of declining to reach a prosecutorial decision, he could have stated which obstructive acts he would have liked to charge, and then said he was declining to bring an indictment because of DOJ policy. Or he could have actually recommended charging Trump, knowing full well that Attorney General Bill Barr would have blocked the move.

Republicans would actually have hated either of these options much more than the status quo. But it would have been better for Mueller. He could then defend the decision clearly based on principles of equality under the law, and his testimony could have focused much more on the facts at hand. Instead, the hearing was mired in hard-to-follow discussions about Mueller's decision that, out of fairness to the president, he would refuse to reach a prosecutorial decision.

This would have been better for Democrats, too, who were forced to awkwardly phrase their questions Wednesday to avoid asking Mueller to answer anything that he had already determined out of bounds. It would have been much clearer for voters and the country if Mueller had just articulated explicitly the crimes that he thought Trump was guilty of, and he had discussed those openly with the committee.

4. The obstruction of justice evidence against Trump is damning.

Nevertheless, confusing as it was, the hearing was illuminating. Even if you've read the report, it's still stunning to see the many instances of potential obstruction of justice by the president detailed on live TV. Democratic lawmakers repeatedly walked Mueller through specific parts of his report that describe Trump's conduct, as well as the analysis that shows the conduct included all three elements for an obstruction of justice charge. For those not very familiar with the investigation, it was a deluge of damning revelations.

5. Mueller thinks the focus should be on Russia — but Trump is in the way.

Many observers noted that Mueller seemed much more animated, lively, and engaged during the second part of the hearing, which focused on matters related to Russian election interference than he was during the first part, which focused on Trump's obstruction. In part, this may be a function of the awkward dance Mueller had to engage in to avoid accusing Trump of a crime, but it also suggests, along with other of Mueller's statements, that he thinks the biggest takeaway of his report should be about the foreign efforts to interfere in American democracy.

But if this is correct, it seems to be another miscalculation on Mueller's part that is compounded by his failure to accuse to Trump of a crime. When it comes to addressing the threats to American democracy, Trump himself is the biggest obstacle, not public understanding or congressional gridlock. The trouble is that Trump doesn't care that Russia interfered in 2016.

Indeed, he'd be happy if Russia tried to help him again in 2020.

And this is why the obstruction investigation was at least as important as the election interference investigation. Trump's apparently criminal obstruction was his attempt to cover up the election interference and the extent of his campaign's involvement in it. Now that it seems Trump won't be punished, he wants to let it happen again. By letting Trump get away with his abuses of power — as Congress is doing, potentially aided by Mueller's reticence — we guarantee that the election interference problem won't be addressed.

6. Trump will declare victory no matter what.

After the testimony, Trump declared that his side "had a very good day," and he panned Mueller's performance. While the hearing did not produce the fireworks some might have hoped for, it was, in fact, a powerful recitation of facts that were damning for the president.

Trump's spin, of course, is entirely transparent. He had claimed that Mueller's report "exonerated" him — a blatant lie. Now that Mueller has sat before the American people and declared that, in fact, he did no such thing, Trump thinks he can just declare victory again.

7. There are other FBI counterintelligence investigations ongoing about... something.

One of the most provocative and surprising revelations of the day came when Democratic Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois questioned Mueller about former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn's lies.

“Individuals can be subject to blackmail if they lie about their interactions with foreign countries, correct?” asked Kirshnamoorthi.

“True,” said Mueller.

“For example, you successfully charged former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn [with] lying about his conversations with Russian officials, correct?” added the lawmaker.

“Correct,” said Mueller.

“Since it was outside the purview of your investigation," Krishnamoorthi continued, "your report did not address how Flynn’s false statements could pose a national security risk because the Russians knew the falsity of those statements, right?”

Mueller's response came as a surprise.

“I cannot get into that, mainly because there are many elements of the FBI that are looking at different aspects of that issue,” he said.

Krishnamoorthi asked: “Currently?”

Mueller confirmed: “Currently.”

It's not clear exactly what Mueller was referring to, but this seemed to indicate that the FBI is still pursuing counterintelligence questions about whether members of Trump's team — Flynn specifically — were blackmailed or became national security threats because of their lies.