The conventional wisdom is wrong--today's Democrats are more united in support of organized labor than the New Deal Dems

False nostalgia is the enemy of sober strategic thinking. With the labor movement under assault from the Trump administration and a Supreme Court twisting the law to undermine unions, it’s become conventional wisdom in some quarters that the fault lies in the disappearance of Democrats of the New Deal variety, the “New Deal liberals [who] did not hesitate to regulate the labor market,” as writer and New America co-founder Michael Lind has argued, contrasting it with the supposed failure of modern Democrats.

Or as Thomas Frank argued more recently, “there was a transition in the Democratic Party in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s where they convinced themselves that they needed to abandon working people” and marginalized labor issues as a party.

The problem with this story is that it both paints a false picture of a Democratic Party united in support of labor unions up through the 1960s and misses the fact that support for labor is actually more of a universal trait among Democratic elected officials today than it was during the New Deal and its aftermath.

New Deal Democrats didn’t all embrace labor rights

The passage of the National Labor Relations Act--the so-called Wagner Act--in 1935 is often seen as the signature achievement of the New Deal-era Democratic Party that paved the way for labor power and higher living standards in the post-war era. But at first it was not seen as particularly radical given the relatively marginal power of the labor movement at the time of its passage. For many legislators, its purpose was as much about regularizing sometimes chaotic strikes of the period and maintaining “industrial peace,” in the words of the statute, as opposed to simply strengthening labor’s ability to battle its corporate opponents. The law passed without opposition by a voice vote in the House and with overwhelming support in the Senate. The small group of lawmakers who opposed the measure were made up equally of Democrats and Republicans. FDR deserves credit for giving unions a rallying cry, but it was not a starkly partisan position at its inception.

What was a political shock was the launch of the left-led Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), with its mass sit down strikes and the surge of new union organizing that engulfed the nation in the next few years. In just ten years, the number of union members in the nation would increase from just 3.5 million in 1935 to 14.3 million in 1945, a number and density across industries that would establish the wage, health care and pension standards that would be seen as the hallmark results of the New Deal.

The ostensible abandonment of the labor movement was not, however, begun by “New Democrats” in the 1970s but in fact was most intense right after World War II when, responding partially to a new wave of postwar strikes, a new Republican-led Congress enacted the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, a law which sharply limited the right to strike, allowed states to establish right-to-work laws to undercut union funding, strengthened management rights to undercut union organizing, excluded or limited a range of workers from the right to form unions, and flat out denied all rights under the law to unions with any Communists in leadership positions – which led to the destruction of multiple unions in the first wave of Cold War anti-Communism.

While President Harry Truman vetoed the bill, a majority of Democratic House members supported the override of his veto and a near majority of Senate Democrats (20 out of 42) voted against the unions to make Taft-Hartley the law of the land. Joining his fellow House members in overriding Truman’s veto was Lyndon Johnson, one of many “New Deal Democrats” who turned on labor.

Democratic votes against labor during this period came almost exclusively from the South, but this was an anti-union Democratic “South” that stretched from New Mexico to Missouri to Maryland. That Southern elected officials made up such a large portion of the Democratic Party delegation in Congress had notably undermined racial equity in a range of New Deal initiatives and would continue to undermine both civil rights and pro-union initiatives for decades.

Twelve years after Taft-Hartley, a majority of Democrats in the House and the overwhelming number in the Senate would vote for passage of the Landrum-Griffin Act of 1959, which would further limit the right to strike and to picket in support of organizing. The bill had emerged from hearings overseen by Arkansas Democratic Senator John McClellan, a strong anti-union proponent of Right-to-Work laws. Nonetheless, he was given the chairmanship by the Democratic leadership of a Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management empowered to investigate corruption in the labor movement. McClellan brought in as chief counsel Bobby Kennedy, who at this point in time brought a decided distrust of union leaders to the investigations, which would lead to headline-grabbing confrontations between Bobby and Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa.

Bobby’s brother, Senator John Kennedy, would initially promote a bill focused on greater union transparency and democracy, but Republicans allied with anti-union Democrats to hijack the process by adding anti-strike and anti-picketing amendments. Nevertheless, when Landrum-Griffin came to a final vote, every Democratic Senator except one voted for the bill despite those added anti-union amendments. (51 House Democrats would vote No on the bill.) Notably, this was a Democratic-controlled Congress with Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson floor-managing a bill for which John Kennedy had been a key initial floor leader. A year later, both were on the Democratic Party’s Presidential ticket despite both supporting a bill that the labor movement had strongly opposed.

The result of Taft-Hartley and Landrum-Griffin were clear. The upsurge in new industries being organized under the National Labor Relations Act came nearly to a halt, with plans after World War II to launch a large-scale organizing drive among workers in the Southern states abandoned. Beginning in 1954 when the percentage of wage and salary workers in a union was 34.8 percent, the unionization rate would begin its inexorable descent. By the end of Johnson’s Presidential term in 1968, the percentage of wage and salary workers in a union had plummeted to under 28 percent and would continue dropping in the coming decades.

The appointment of a series of Republican Supreme Court and lower court judges who would interpret the laws even more unfavorably to labor interests, along with the particular assault on labor under the Reagan administration, would do additional damage. But a declining union movement was not the product of “New Democrats” turning against labor -- it was baked into the system by the immediate post-WWII era of Democrats stabbing labor in the back and weakening labor laws.

Support for labor has increased steadily among modern Democrats

Relations between unions and the Democratic Party leadership would remain fraught in the two decades following Landrum-Griffin, especially as the Vietnam War and other conflicts over civil rights, women rights and the environment split the Democratic Party in the 1960s and 1970s, leading to the AFL-CIO refusing to support George McGovern for President in 1972, the only time the federation sat out a Presidential election.

Yet beneath that conflict, as the southern wing of anti-union segregationists declined, the Democratic Party developed a greater consensus in support of union rights. The last fifty years would see a series of attempts by modern Democrats to pass labor law reform bills to partially reverse the damage done by Taft-Hartley and Landrum-Griffin, while those same Democrats would block every attempt to enact significant new anti-union legislation. Under Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and in 2007, increasing numbers of Democrats in both houses of Congress would vote in support of labor law reform, only to see the bills defeated by filibusters.

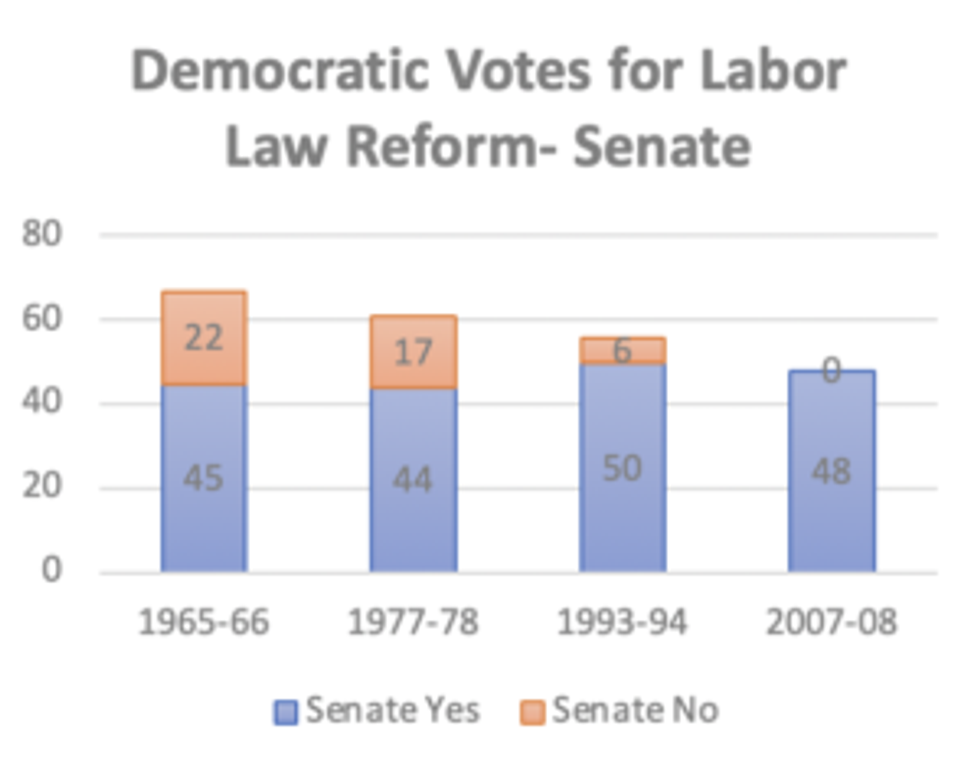

In looking at the following charts, what’s notable is how stable the number of pro-labor Democratic votes there have been across recent decades with a small but notable increase in the number of pro-union Democratic votes matched by a massive decline in anti-union Democrats in office. In fact, it was under “New Democrat” Bill Clinton that, for the first time since passage of the Wagner Act itself, you had 50 Democratic Senators supporting a significant bill to strengthen private sector organizing. It’s worth repeating that—in the 1940s and 1950s, there were Democratic majorities for gutting labor power and in later decades, there still were not 50 Democrats in the Senate to support new pro-labor laws in the whole period from 1935 until 1993.

Part of the story of modern politics is that many of the anti-labor Democrats who joined with Republicans back in the 1960s and 1970s to filibuster labor law reform were replaced by new anti-labor Republicans to the point where there were no Democratic votes against labor law reform in the Senate in 2007 and only two anti-union votes in the House that year. At the same time, Democrats were strengthening their hold in pro-union states in the North as the last of the pro-union Republicans disappeared from modern politics.

And with the Voting Rights Act expanding the southern black vote, which was far more inclined to support pro-labor politicians than their white southern compatriots, you began to have a significant number of pro-labor Southern elected officials. By 1978, you had border state Democratic Senators in Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and Tennessee supporting labor law reforms and by 1993, you would have Democratic Senators from Alabama, Louisiana, New Mexico and Virginia supporting labor law reforms as well. By 1993, the House had pro-labor Democratic votes in new black-majority districts throughout the Deep South.

Strengthening Democratic electeds’ support for labor in the 1990s were changes within the labor movement itself and a deepening of alliances between labor and other Democratic Party constituencies in the environmental, anti-war, civil rights and immigrant rights communities.

When John Sweeney won the first significantly contested fight for President of the federation since the AFL-CIO merger, one of his first acts was to dissolve the Cold War, CIA-affiliated labor “institutes” that anti-war critics had long denounced. Sweeney himself joined the Democratic Socialists of America, the home of many internal union critics of the AFL’s previous foreign policy. Where US unions historically had an uneven history of support for new immigrant workers, in 1994 California unions allied with immigrant rights groups to fight the anti-immigrant Prop 187 and the AFL-CIO executive council made strong support for immigrant rights national labor policy in 2000. And a new Blue-Green Alliance of labor and environmental groups emerged supporting green jobs initiatives in multiple states, while enviro-labor coalitions started challenging US trade policy, culminating in the “Teamsters and Turtles” direct action in the streets of Seattle to challenge the World Trade Organization talks in 1999. This all gave labor stronger alliances in holding Democratic elected leaders accountable in supporting labor’s political agenda.

After the chill of the George W. Bush Presidential administration, labor had high hopes with Obama’s election in 2008. Along with Barack Obama’s own election, the 2009-10 session had the highest number of Democratic members favoring labor law reform in the postwar period (an estimated 58 or 59 Senators), but to the frustration of labor advocates, they fell just short of the 60 votes needed to pass the Employee Free choice Act over a Republican filibuster, and didn’t bring the bill to the Senate floor.

Obama’s appointments to the National Labor Relations Board, however, were almost universally praised by labor leaders, and new rules promoted by the NLRB such as speeding up union elections, protecting pro-union speech using company email and holding employers responsible for anti-union actions by subcontractors, were a major advance in assisting labor organizing even in the absence of legislative changes. And notably, when the Republican majority in 2015 voted to roll back many of these new NLRB rules, not a single Democrat in either the House or Senate supported the effort, ensuring that Obama’s veto of the measure would be sustained. Similarly, when the Republicans in 2017 did roll back a number of Obama’s pro-labor rules, again not a single Democrat supported the GOP’s assault. There is a unity in defense of labor interests in the modern Democratic Party that was nowhere to be seen during the New Deal era.

How Democrats in the states stepped up to support unions

Where modern Democrats have made a more significant difference in union membership numbers has been at the state government level. While federal labor law restricts how much states can intervene to help (or hurt) private sector unions, state right-to-work laws are one of the most impactful tools undermining unions, while “Davis Bacon” laws requiring private construction firms working on public buildings or transit projects to pay union wages are a powerful tool given that as much as one-fifth of all construction has used state or local funds over the years. Republican-controlled states have expanded right-to-work laws and repealed Davis-Bacon laws, leaving an increasing partisan divide among states.

However, the largest impact states have had on union membership rates has been through legalizing public employee unions. Public workers were excluded from union protection under the National Labor Relations Act and only 2 percent of state and local public employees had the legal right to collective bargaining in 1960. By 2010, that number had grown to 63 percent as states enacted their own laws recognizing the right of state and local workers to form unions. The main reason America’s unionized workforce hasn’t plunged even further is because the rise in public sector union rates counterbalanced some of the decline in the private sector. By 2015, 42.3 percent of all union members were organized under various state statutes, not under the federal NLRA.

It is largely in the Democratic-led states that public sector union density and support for private sector unions has been highest. Most recently, those Democratic-led states have promoted unionization in industries funded with public dollars such as home health care by declaring those employees to be public sector workers with the right to unionize under state law—a far easier task in most cases than under federal labor law.

After pioneering states like California promoted this strategy, about a dozen state governors, all Democrats, would issue additional executive orders from 2003 to 2011 allowing home health care workers to unionize under state law, while Republican successors in states like Ohio and Michigan would cancel the orders. Overall, an estimated 25 percent of home-care workers nationwide belong to a union—a significant number in an industry expected to reach 3.2 million workers by 2020. Similar strategies have been applied to day care workers and some states are discussing extending union rights to Uber drivers and other independent contractors, who are also excluded from NLRA protections.

This partisan divide in support for labor is reflected in the stark differences in unionization rates between Democratic and Republican-leaning states. In the “Blue Wall” states that have consistently voted Democratic in the last seven Presidential cycles, 15.8 percent of wage and salary workers are in unions, nearly three times the 5.5 percent unionization rate in the “Red Wall” states that consistently vote Republican.

That unionization rates between the states range from a low of 2.1 percent in South Carolina to a high of 24.7 percent in New York state reflects that progressive state policy has played a significant role in strengthening labor rights despite the weakness of federal labor law itself. In fact, when you compare unionization rates in Blue Wall states, they don’t look out of place compared to many European countries and New York’s union membership is higher than quite a few countries in Europe. There is no overall “U.S. exceptionalism” discouraging participation in unions, just a “red state” exceptionalism where hostile conservative policy has undercut even the weak protections in federal law. That said, weaker labor law in the U.S., which does not encourage industry-wide collective bargaining agreements as in much of Europe, means that fewer workers overall end up protected by union contracts in the U.S. than European states with similar union membership rates.

While labor unions have experienced a significant decline in membership over the decades, a decline shared with many European states as well, the fact remains that Democratic leaders in recent decades have played a significant role in stemming those losses in states where they had political power.

And if you compare unionization rates of public employees, where US states have essentially similar legal power as European states, Democratic leaning states are generally more unionized than in Europe, with states like New York and Connecticut pushing into the Scandinavian league of unionization.

The recent Supreme Court ruling in Janus undermining public sector unions is likely to undercut those numbers, but that highlights the real situation labor has faced— generally pro-labor policies promoted by the Democratic Party repeatedly blocked by anti-democratic means such as the US Senate filibuster and the Supreme Court.

What’s next?

Given the passage and expansion in the modern era of civil rights legislation, age discrimination legislation, disability rights protections, pregnancy discrimination laws, the passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Family and Medical Leave Act, the argument by some critics that Democrats abandoned workers issues is on its face perplexing.

And as the above history emphasizes, it is just as nonsensical, as a recent headline in New York Magazine did, that Democrats “let” unions die.

There is a stronger argument that Democrats once they finally had fifty votes for labor law reform under Bill Clinton – and to repeat that was the first time since the Wagner Act that this was true – they should have seized the moment to abolish the filibuster and pass labor law reform.

However, there were then and remain many liberals who defended the filibuster under Obama as a last ditch defense of other progressive policies for fear of when Republicans took back power (even if experience under Trump has shown how thin a hope that remains). As well, wavering moderate Democrats also see the filibuster as a tool that strengthens their political hand within the caucus, so are loathe to provide the votes to abolish it.

Pro-labor activists should be making it a priority to convince Democratic defenders of the filibuster that once we have a Democratic majority in Congress again that it is worth the risk to abolish the filibuster and pass labor law reform, all with the hope it might spark a CIO-style resurgence of labor power and an associated surge of progressive grassroots political strength.

We don’t need a faux nostalgia for a non-existent past in the Democratic Party to make that argument, but instead can point to commitments to labor that Democratic legislators are working to fulfill throughout the country in the states – and which the filibuster and lack of federal labor law reform is undermining at the federal level.

Abandoning that false nostalgia also means abandoning the rhetorical argument that a “better” Democratic Party is all or even the main thing needed for helping strengthen the labor movement. Getting more Democrats elected in districts and states currently controlled by Republicans is the key to building the majority needed at the federal level to pass labor law reform – and to rein in a Supreme Court threatening any legislative achievements that might be made.

There’s no question that once basic labor reforms are enacted, more moderate Democrats will end up being a break on expanding labor power too far. But we are quite a few steps from that point, so while there is good reason to keep organizing in Democratic primaries to elect more strong progressives, the immediate challenge is getting more Democrats elected overall in the nation.

Teachers strikes that swept red states in recent years show that there is a base for building stronger pro-labor alliances in GOP-dominated states. Supporting elected leaders to represent the voices of those movements should be a top priority. That is the route to building a Democratic majority that can force through legal changes that can further strengthen the organizing and negotiating power of unions versus employers around the country.