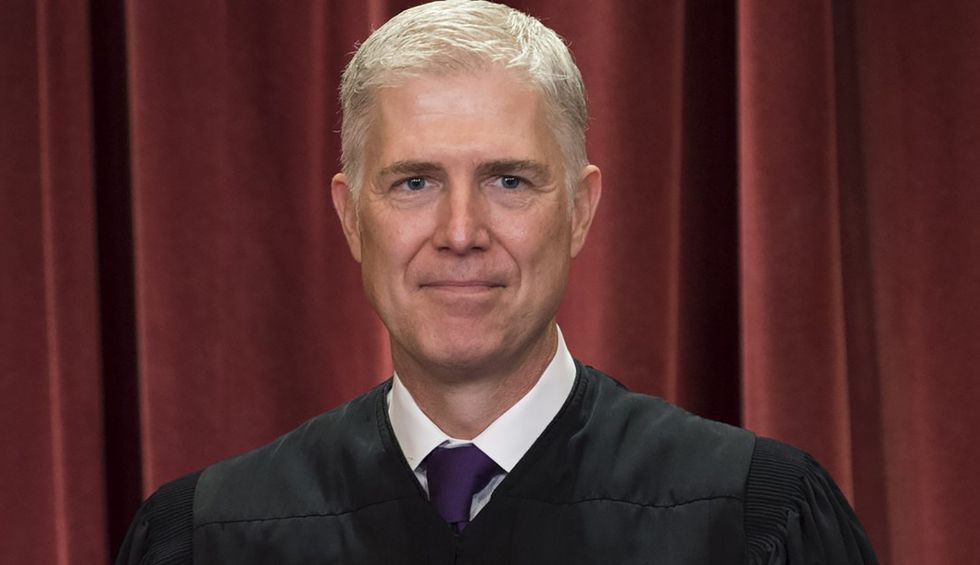

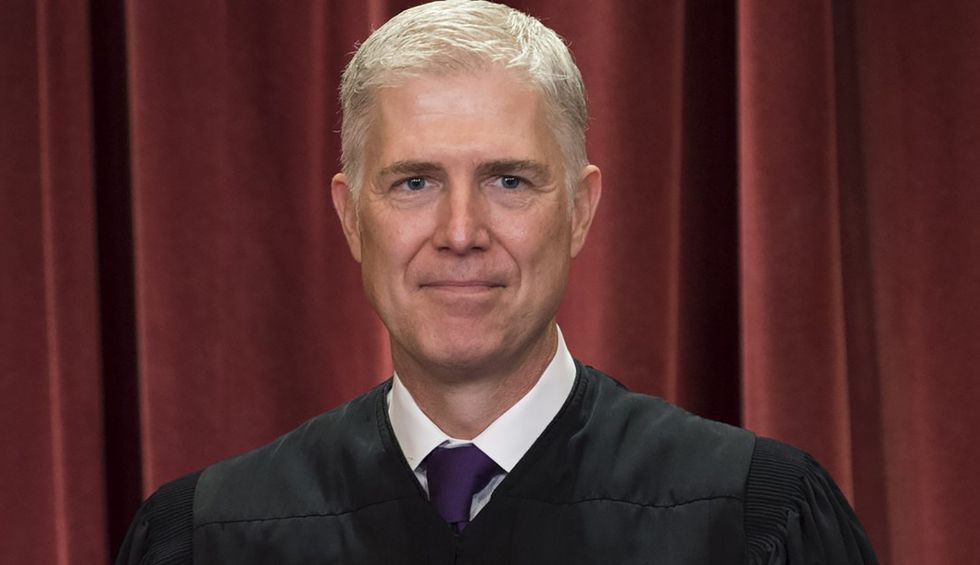

Constitutional law professor explains why Neil Gorsuch’s ‘proud textualist’ approach is built 'on quicksand'

Justice Neil Gorsuch recently infuriated far-right social conservatives when he wrote the U.S. Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County and ruled that LGBTQ residents of the U.S. were protected against workplace discrimination. Fundamentalist evangelicals felt betrayed, but Gorsuch’s defenders argued that he arrived at his decision because he is a “textualist.” Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston, examines Gorsuch’s judicial philosophy in an article published in The Atlantic — and poses the question: how should a textualist deal with problematic case law?

“Justice Neil Gorsuch is a proud textualist,” Blackman writes. “According to this approach, what Congress intended or expected when it passed a law doesn’t matter. What matters are the words printed on paper. In practice, Justice Gorsuch will strictly follow the text of statutes, no matter what result it yields. Last month, he decided that the 1964 Civil Rights Act has always prohibited LGBTQ discrimination — everyone had simply missed it for half a century.”

In Bostock v. Clayton County, Blackman notes, Gorsuch “insisted he was sticking to the text, the whole text and nothing but the text. Alas, he wasn’t.”

According to Blackman, Gorsuch’s “interpretation was shaded by the work of justices who had not been so careful about text. …. Justice Gorsuch failed to acknowledge that the Court’s precedents were inconsistent with textualism. In doing so, he inadvertently undermined textualism’s justification. One can’t profess to follow the original meaning of a text while, in fact, following precedents that ignored that meaning.”

Gorsuch, Blackman adds, “did not begin his analysis” in Bostock v. Clayton County “by interpreting this text on a blank slate. Rather, he simply assumed that decades of case law had accurately interpreted the crucial phrase ‘discriminate against because of sex.’ Indeed, he treated decades of precedent as part of the ‘law’s ordinary meaning’ in 1964. This approach built an elaborate textualist framework on quicksand.”

For textualists, Blackman notes, a “fluid approach” is a “bitter pill…. to swallow” — and Blackman explains how Gorsuch’s approach in Bostock compared to his approach in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which dealt with Native American territories.

“In Bostock,” Blackman writes, “Justice Gorsuch quietly accepted precedent that paid little attention to text. In McGirt, he quietly rejected precedent that paid little attention to text. In both cases, he erected elaborate textualist structures on top of a foundation well worn by the Court’s prior decisions. And in neither case did he acknowledge the relationship between precedent and textualism.”

Blackman concludes his article by arguing that Gorsuch sometimes practices “precedentialism” rather actual textualism.

Gorsuch, according to Blackman, “preaches textualism, but practices precedentialism. This approach, in the long run, will serve only to undermine textualism. If Justice Gorsuch wants to move the law away from nebulous, flimsy reasoning toward more textualist, neutral principles, he must account for both text and precedent.”