An obscure 1800s law is shaping up to be the center of the next abortion battle: legal scholars

Sonia Suter, George Washington University and Naomi Cahn, University of Virginia

Anti-abortion groups are looking for new ways to wage their battle against abortion rights, eyeing the potential implications of a 150-year-old law, the Comstock Act, that could effectively lead to a nationwide abortion ban.

Congress passed the Comstock Act in 1873, making it a crime to mail or ship any “lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy or vile article” and anything that “is advertised or described in a manner … for producing abortion.”

There are now legal cases questioning the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of mifepristone, one of the two drugs used in the standard regimen for medication abortion. If courts find that the FDA has the authority to approve mifepristone for abortion, the Comstock Act could still prevent the pill’s distribution.

As scholars of law and reproductive justice, we have been analyzing potential strategies to use this Victorian-era law to restrict the ability to get an abortion in the U.S.

Read one way, the Comstock Act could prevent mailing mifepristone to a person’s home, regardless of whether this person lives in a state where abortion is legal.

A broader interpretation, advanced by anti-abortion groups in recent months, would mean the Comstock Act applies to the distribution of all drugs and medical tools used for abortions, not just mifepristone.

The Supreme Court returned the question of abortion rights to states in June 2022. But it’s important to understand that the Comstock Act is a federal law that applies to states, regardless of their approach to abortion.

So while abortion remains legal in certain states, we believe it’s possible that a court could interpret the Comstock Act to prevent the distribution of any tool used for an abortion, anywhere in the U.S.

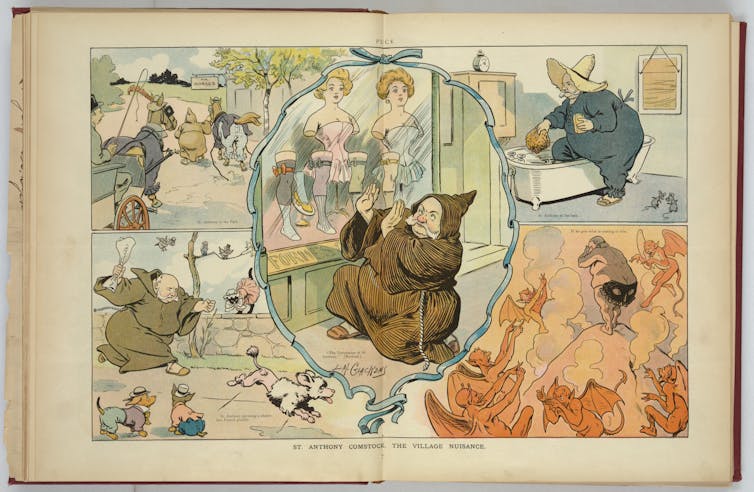

A 1906 illustration shows Anthony Comstock, center, thwarting excessive displays of flesh, be it a woman, dog or horse.

The history of the Comstock Act

Devout Christian and self-described “moral evangelist” Anthony Comstock came up with the idea of what would become the Comstock Act after he felt troubled by the large amount of pornography and alcohol his fellow Union army soldiers consumed.

He lobbied for Congress to pass a law restricting what he deemed lewd behavior, displaying “his impressive collection of pornographic pictures, sex toys and contraceptive materials” in the Capitol building “to help galvanize Congress to pass anti-obscenity legislation.”

Congress then passed the Comstock Act in 1873.

Although prosecutions under the Comstock Act were brought in the early 1900s, enforcement started to wane by the 1930s.

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has heard the occasional case related to the law over the past 100 years. In 1983, for example, the Supreme Court found that applying the Comstock Act to prohibit mailed advertisements about contraceptives violated the First Amendment.

No court has since ruled decisively to actually enforce the Comstock Act.

Indeed, major court decisions have limited the law’s applicability.

And, in 2022, the Justice Department issued an opinion concluding that the Comstock Act does not prohibit mailing mifepristone if the sender doesn’t know the recipient intends to use those pills “illegally” for abortions – for example, the recipient might be using them to treat a miscarriage.

Applying the Comstock Act today

As anti-abortion rights groups try to reinvigorate the Comstock Act, the question is what the law covers, exactly. Several legal cases are addressing this point in different contexts.

Texas federal court Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk – who issued a preliminary decision on April 7, 2023, effectively rescinding the FDA’s approval of mifepristone – said the Comstock Act prevented the mailing of abortion pills.

When that decision was appealed, the appellate court seemed to agree with Kacsmaryk. It noted that the law does not necessarily require users “of the mails or common interstate carriage to intend that an abortion actually occur,” contrary to the Justice Department’s 2022 opinion. It emphasized, however, that it was “not required to definitively interpret the Comstock Act” because it was not issuing a final ruling.

That decision was then appealed to the Supreme Court, which temporarily upheld the availability of mifepristone and sent the case back to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals for full review on April 21.

The appellate court will hear oral arguments on May 17 and should issue a more definitive interpretation.

Extending to other lawsuits

The Comstock Act is also at the center of other kinds of litigation and legal campaigns focused on whether people can get abortions.

Jonathan Mitchell, a conservative lawyer and former solicitor general of Texas, is trying to use the Comstock Act to outlaw abortion altogether. Notably he also devised the Texas “bounty-hunter” abortion legislation in 2021 that bans most abortions and “deputizes citizens to sue people involved in the process.”

Since 2019, two counties and more than 60 cities in Texas, Nebraska, Iowa, Ohio, New Mexico, Louisiana and Illinois have passed ordinances that ban abortion. This is part of a political campaign called Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn – orchestrated by Mitchell and conservative pastor Mark Lee Dickson.

Some of these places now prohibit the shipment and receipt of abortion drugs or medical items used for abortions.

These ordinances have led to two lawsuits questioning their legal status.

New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez sued several Sanctuary City towns in January 2023, claiming that the ordinances violated state law that says people have the right to access health care and that physicans’ care of patients is a private matter.

But then the New Mexico city of Eunice, another Sanctuary City, also filed a lawsuit in April 2022, asking a state court to determine that the Comstock Act is enforceable.

Finally, the Comstock Act is being applied even after an abortion has occurred.

In a Texas lawsuit filed in March 2023, Texas resident Marcus Silva sued three women for wrongful death, saying they assisted in “murdering Ms. Silva’s unborn child with illegally obtained abortion pills.” The complaint notes that Silva will also sue the pills’ manufacturer for wrongful death based on the Comstock Act.

An advertisement outside a pharmacists conference in Phoenix advocates for the safety and necessity of mifepristone.

Chris Coduto/Getty Images for UltraViolet

Mailing, distributing or banning?

It seems likely that the high-profile federal FDA mifepristone case in Texas could head back to the Supreme Court after the 5th Circuit issues its ruling. If so, the Supreme Court could determine that the Comstock Act only applies to the mailing of items if the sender knows the items are intended to be used “illegally” for abortions. In that case, little or nothing would change in states where abortion is legal.

Or, the court could decide that the Comstock Act bars mailing mifepristone regardless of its user’s intent, making access to medication abortion more difficult. The court could also cast a wider net, prohibiting the shipping of abortion medication altogether across the U.S.

And if the Comstock Act applies to mifepristone, it could also apply to any other item or tool that is used to terminate a pregnancy. Such a ruling would effectively impose a nationwide ban on abortion, even in states that allow abortions. To achieve this result based on an 1873 Victorian statute would be entirely consistent with Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade based on the state of the law in 1868.![]()

Sonia Suter, Professor of law, George Washington University and Naomi Cahn, Professor of Law, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- 'Not realistic': Nikki Haley won’t endorse national abortion ban ›

- Chief Justice John Roberts’ anti-abortion activist wife may have 'influenced' his 'judicial decisions' ›

- Anti-abortion activists take direct aim at contraception: report - Alternet.org ›

- 'Losing it mentally': Federal judge’s forced retirement leads to bitter battle - Alternet.org ›