Maggie looked like the typical housewife next door in a suburban community. No one but an experienced user might guess she had injected methamphetamine almost every day during the last six months. She looked younger than her forty-seven years, and her easy smile revealed strong white teeth, inconsistent with the pictures of toothless “faces of meth” displayed on highway billboards by anti-meth campaigns. She looked as if she had just stepped out of the beauty salon with her stylish haircut, manicured nails, and just enough makeup to accent her best features. Maggie was very personable, and we quickly developed affinity over common concerns for people with drug problems. Some of the suburban women I met were reluctant to open up about their personal lives because of the social stigma of their drug use, and it took time to develop a trusting relationship with them. I did not have this problem with Maggie. Her frank turns of phrase, amiable demeanor, and candid communication style conveyed a sense of camaraderie that engendered trust. Having already established good rapport with Maggie, I did not think she would be offended when I asked if her beautiful teeth were her own. “Yeah, I got all my own,” she replied, with a smile that reassured me she understood why I had asked. Tooth decay was a common problem among methamphetamine users.

Maggie lived most of her life in the same suburban area where she lives today. She was close to her family, especially the grandmother she cared for until her death. She had three children and was extremely bonded to her family and loved ones. Her otherwise conventional suburban life included dealing cocaine and methamphetamine, which supplemented her husband’s income.

Compared to many drug users, Maggie started her drug career relatively late. Believing the anti-drug warnings she had heard in high school, she never used marijuana, which she called pot -- the slang term used by her generation. It was not until she graduated from high school that she tried pot at a party, mainly because she did not like to drink alcohol. She discovered that marijuana did not give her the stomach problems she got from drinking, and it made her feel relaxed and more sociable. She also experimented with a trendy drug at the time, Quaaludes (methaqualone), available in pill form, for much the same reason she used marijuana occasionally -- they were a depressant but did not give her a hangover.

Buy the book:

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"full","fid":"554106","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"250","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"300"}}]]

Illegal drugs were used in her social network and offered to her at different points in her life. Typically, drugs held no appeal when she first tried them. For example, Maggie experimented with a homemade type of methamphetamine, known as crank, a few times as a young adult, but she never liked it. The motivational push that led to her continued use of methamphetamine came years later when she was a young mother. Trying to lose weight after having kids, she sought help from a doctor. Like many women who marry, have children, work at home, and live in suburban communities where errands and shopping are done in a car, Maggie had little time or opportunity for physical exercise, and she gained more weight than she wanted. Her plump figure put a damper on what was otherwise the perfect suburban housewife role she adeptly occupied.

In our society, the symbolic wife is expected to keep a clean house, cook delicious and varied meals, help with the children’s schoolwork and extracurricular activities, uphold the family’s social reputation, and contribute to the household income by holding a flexible job with little career opportunity. Beyond this, the postmodern wife is expected to be a ready and prepared sex partner with a model figure at any age. A television show popular early in the twenty-first century, Desperate Housewives, depicts this type of suburban woman with an edgy twist but lacks the “supermom” role most real suburban mothers have to maintain. Maggie’s story was not far removed from the script of this television phenomenon. To help her lose weight, the doctor prescribed diet pills. When she moved and could not find a doctor who would give her a prescription, a friend offered her a drug that was better and cheaper -- and that was her first taste of a form of methamphetamine called ice: “At that time a quarter gram was fifty dollars. I was like, wow. And having done crank, I was like, what? Crank was okay, but I didn’t like it. That was really what they call bathtub crank, and I mean it could kill you. It was like lye and acid and all this other stuff. Whereas ice was supposed to be something that you could do one line and be up twelve hours.”

Maggie used ice occasionally to lose weight and keep trim. She started regular use of the drug because it helped relieve her depression. Although typically an extrovert, who described herself as a “social person,” she entered an emotional slump and stopped participating in many social activities after her grandmother’s death, which was followed by the death of another close relative. A doctor prescribed Paxil, but Maggie soon discovered that ice made her feel better: “I was the kind of depressed that a hairbrush would be sitting there and it was just like heavy to pick it up. I couldn’t even pick it up. It was like I didn’t even want to go out. I didn’t want to do nothing. And they put me on Paxil, and it just didn’t seem to be getting it ... and I did ice and I started getting up, and I started being social again.” It was easy for Maggie to obtain ice in her suburban neighborhood. Methamphetamine was being called an epidemic by the local the newspaper and police in this southeastern region of the United States, where federal funding for anti-meth campaigns and special law enforcement task forces helped to focus attention on this emerging drug problem.

Maggie started using methamphetamine fairly regularly, but in her mind, ice was a functional drug rather than a recreational one. Her husband worked in hard physical labor and he used ice to help him work even harder and longer hours. Together, he and Maggie managed to start two successful businesses: one legitimately and the other covertly.

Their illegitimate business was not part of their original business plan, but it helped them maintain their middle-class status. Maggie learned that her neighbors were selling cocaine from their house. She tried cocaine a few times, but she never used it regularly. When her neighbors discovered she was good with math, they asked her do the accounting for their underground business. She could use the extra money. Eventually, Maggie and her husband started dealing cocaine to supplement the money he made from their legitimate small home business. “It’s unbelievable what you can do. Because I mean I could break it down by how many quarters or how many sixteenths. ... We were dealing so much my husband was like, ‘we could quit work.’ And I was like, ‘no, no.’ He called me at lunch and I said I made five hundred dollars already, and he’s like, ‘what?’ And I’d still have dinner cooked and still be at the PTA. I was mother of the year and volunteer of the year at my daughter’s school. ... We banked close to fifty thousand dollars in a few months.” Maggie and her husband were low-key. Unlike the stereotypical drug dealer, who is often depicted as indulging in his newfound wealth, splurging on luxuries, and arousing the suspicion of the police [...] Maggie possessed social and cultural capital that not only enabled her to bridge diverse social networks but also provided the skills and understanding needed to maintain her middle-class status. With her strong background in the values, beliefs, and behaviors learned from her middle-class parents and grandparents, she embraced the norms of modern suburban living that developed over the last century throughout the U.S. social landscape. Whereas many of the other drug dealers I had met spent their money on transient pleasures that drained their assets, while simultaneously attracting the attention of drug enforcement officers, Maggie knew better.

Avoiding the trappings of the suburban nouveau riche, Maggie used the extra money made from drug dealing to save for unexpected family expenses, such as hospital bills, and started saving for her daughter’s college fund. Maggie and her husband eventually saved enough to buy a house. Their middle-class dealing activities stayed well under law enforcement radar, and since cocaine was not her drug of choice, she never used up their supply or secretly cut their product to cheat customers and keep more for personal use, which was a common practice according to stories I heard from other suburban drug dealers. Maggie also seemed to be able to control her methamphetamine use behaviors. Even though she used almost daily, she never binged. Her husband did not have an addictive personality: “My husband is the type that can do it once a month, maybe two. I mean if it was just left up to him, he’d never do drugs again.”

Maggie’s peculiar yet tranquil suburban life was shattered when accumulated family tragedies instigated her deep depression. She tried to commit suicide with prescription pills but woke up in the hospital instead. During her fight for life in the intensive care unit (ICU) of the hospital, she saw her deceased relatives in a vision:

They brought my family in to basically say good-bye and I came to, because my youngest daughter was sitting there saying, “Mom,” and they were taking the tubes out of me at the time, and the nurse was, I remember, the nurse hollering for the doctors ... and I remember I had blisters from the tubes in my mouth and pneumonia in both my lungs when I came to from the ventilator, you know, the machine doing all my breathing. I remember cause I’d had a conversation earlier that crossed -- that experience, it wasn’t the light and all -- but I remember having a conversation with my grandmother right before I came in, and I don’t know if it was a dream. I don’t know if it was the actual vision or whatever, but I do remember her telling me to get out of here, “You’re not welcome here. Go. Go. Go!” And I know they were trying to get rid of -- trying to make me come back is what I feel like. And my grandmother wouldn’t look at me. She just kept looking down at the ground, but if she [had] looked at me, I think I wouldn’t have come back because I wouldn’t have wanted to.

Maggie revealed that after this vision she realized, “God had a purpose in my life.” But it did not stop her from continuing her use of methamphetamine, which she felt she had under control with her newfound belief in the twelve-step philosophy. The juxtaposition of being an ambassador for twelve-step, an abstinence-only model of drug treatment, while still using methamphetamine was just one of the contradictions she revealed.

Maggie’s attempted suicide changed her life. She went to a residential treatment home after the pill-taking incident that had left her in the emergency room. It was here that she was introduced to the support group recovery model known as the twelve-step program. Maggie had always been a person who bonded easily with strangers and bridged social gaps that often divide those of different social status, and she bonded just as easily with her recovery sponsor while embracing the twelve-step program. She told me about her first twelve-step meeting at the residential recovery program, where she honestly revealed in her matter-of-fact way to all that her entire social network was composed of suburban methamphetamine users:

The first thing that they told me when I walked in was they gave me a sponsor, and she turned around, and I mean I was scared to death. She said, “Tomorrow night I want you to come in here with your phonebook. Bring your phonebook in here.” I was like “okay.” I came in here the next night, she hands me a permanent magic marker and she said, “I want you to take this phone book and I want you to mark everybody in that book that uses.” And I looked at her, and everybody was looking at me, and I threw it on the floor. And she said, “Now we have rules, this is how,” and I said, “Oh no ma’am, I got my sister’s number memorized by heart. Everybody else in the book is all users.” And she said, “You got to be kidding me.” And I said, “No ma’am, everybody else is users.” ... And I called every person I know and said, “No, I’m not a narc [undercover drug cop], and no, I didn’t get busted. But I wish you well, and I want you to wish me well. I’m going to try this out [twelve-step]. Remember me telling you I wanted to find out who I am? I’m fixing to try out.” And that’s what I did. And I just -- I love it. ... Yeah, “My Name is Bill.” Bill’s the one that wrote the book, and actually the whole step. It’s a spiritual program. It’s an awesome program.

Maggie became what could be called a twelve-step zealot. She ceased all her drug use and developed a missionary-like calling to help those less fortunate than herself.

Ironically, although her self-proclaimed spiritual experience roused by the twelve-step program led Maggie to acquire the role of a savior for other addicts, she herself began using methamphetamine again -- she relapsed with a peculiar twist. As Maggie described her own recovery path and relapse, and how she “saved” others from self-destruction, her religious fervor caused a change in her previously sincere self-reflective and subdued demeanor. She became visibly energized while she unconscientiously preached the twelve-step philosophy like a convert at a revival meeting. She linked every incident of her own personal story to the story of Bill W, the alcoholic who started the twelve-step program known as Alcoholics Anonymous. For example, when I asked about her relapse, her story was interspersed with twelve-step ideology:

Because when they say you can’t get back around anybody, they really mean, I don’t care how strong we are. It’s like Bill said, “Oh I can go into this bar, and I can sit there and say I don’t have to drink.” Bull! You’re there. Maybe the second time, maybe you think, “Well I’ll just take a sip of it and eat my sandwich.” And the next thing you know you’re drunk, and you’re sitting there, and you’re only fooling yourself ... and I thought, well, I can’t go to the school today to help my daughter unless I have some ice. And I know better, but that’s the mind thing of me saying -- I’m trying to fool myself is what it is.

I pressed her to describe what was going on in her mind when she relapsed:

Well, I was on the way over there [the house of a friend who was a user] and I wanted to prove to them that I could be -- and my husband said, ‘“Don’t go over there.” And I said, ‘“Oh no, I’ve been clean for a year and a half, I’m never going to do ice again. I’ve got sponsors.” I was sponsoring people and I just, I can do this -- I’m thinking now that’s what Bill said when he went into that bar -- I can do this and be the only one in the world that can do it.

Maggie said she felt guilty after relapsing. Although she did not see a relationship between her guilt and her new role as a missionary for the twelve-step philosophy, the two appeared connected in her narrative. Every mention of her current use was linked to how she was going to quit using by bringing another person into the twelve-step program. For example, Maggie had introduced me to a young woman who was staying at her house. The girl’s tiny body belied her nineteen years, and in contrast to Maggie, she looked eerily like one of the “faces of meth” photos I saw on the highway billboards. Maggie explained her current mission with this young woman:

I mean, see poor old Julia. She’s been through hell, and I gave her an intervention. She actually looks better now. She got raped last week over at a friend’s house. And he left, and she was there by herself. And the guy had a grudge against this other guy and came in and raped her in the process of it ... I feel so sorry for her because she is just—she’s alone. Just met her at some friend’s house. I went over there and next thing I know I brought her home ... and I kept trying to tell her, “Julia, you are an addict,” and we [twelve-steppers] are not supposed to call each other addicts. And I keep trying to say [to Julia], “I can’t call you an addict but I’m telling you, from experience, that you need to go [to a twelve-step program], and I’ll take you” ... I love being clean to be honest with you. I know in my heart I like being clean [drug-free] ... I tell Julia all the time. “Shit,” I said, “forget that I’m using.” I tell her all the time, “I’ll go in with you ... when you work the program, when you get to step four, all of a sudden you wake up one day and world is just all out there. It’s like God opens miracles for you.” ... I keep telling Julia to go clean with me, “Julia, you know, when we get to step four [of the twelve-steps], if you are not seeing miracles happening in your life, I’ll go buy your dope [local slang term for methamphetamine] and we’ll go out and get high again.

Though Maggie’s behavior of using methamphetamine while encouraging others to stop using might seem hypocritical, she was truthful about her use. Some might interpret this behavior as dishonesty or a petty excuse to continue using. Yet the sincerity of her confessional belief in the twelve-step program and her candid portrayal of herself as a recovering “sinner” did not give the impression that she was what some women in twelve-step called a poser. Instead, Maggie appeared to be a woman trying to bridge two worlds that held meaning for her but were, unfortunately, incompatible.

To complicate her recovery further, Maggie bonded easily with members of divergent social networks. Maggie displayed unusual social characteristics that can be both helpful and harmful. She seamlessly wove her intimate primary relationships in suburban middle-class networks with her drug-using relationships that bridge legal and illegal activities. She understood the motivations and needs of disenfranchised drug users while embracing the strictly conventional norms of middle-class society endorsed by the twelve-step practice. Therefore, while Maggie appeared to be firmly grounded in the suburban social landscape, her association with many young methamphetamine users influenced her to engage in behaviors that conflict with middle-class conventions. For example, when revealing that she is a daily injector, she explained that she cannot inject herself and asks someone else to do it. Her reasons for injecting methamphetamine instead of smoking or another route were also unusual:

Because it [methamphetamine] was like dirty and ’cause everything filters through the kidneys and liver and all that. I know all that. And when you get bad dope you get kidney infections, or you get backaches, and that’s your kidney, cause it’s filtering through that. I knew that, and I was like, “There’s got to be another way.” That’s when she [a friend] was like, “Well, let me show you.” And I was okay, and then it was like, wow, I can do it once in the morning and I’m fine all day. A lot of people, they do it all day long. Now I’ll do twenty dollars in the morning and I’ll be good all day. I’ll go to sleep at night, go home and eat dinner.

Most of Maggie’s close friends used methamphetamine, and those she came in contact with who were not close (teachers, PTA parents) could not tell that Maggie was on ice. She looked like every other mother, and her behavior did not give her away.

While Maggie talked, I hardly noticed any behaviors that would indicate methamphetamine use, except for the vast knowledge she recounted of every aspect of a user’s life. She sat calmly in her chair during the two-hour interview, except when recounting her twelve-step stories and advocating its philosophy with slogans and quotes she memorized and repeated with an uncharacteristic display of animation. I attributed this to twelve-step enthusiasm more than the influence of methamphetamine. I had met enough twelvesteppers to recognize that her behavior was learned, but it was her otherwise composed state that was more curious.

Daily methamphetamine users were, if not agitated and unable to sit still for long periods of time, often more frenetic in their behavior than Maggie. I had seen this composed nature before among the few women who had been using methamphetamine regularly for years but not in a bingeing pattern of intense use for days. Some women who used in a controlled manner over years even gained weight and said they had little trouble sleeping, which seems contrary to the physical effects common to methamphetamine use. Typically, as tolerance increases, women increased their dose or frequency, but not Maggie. She had learned her lesson. She told me that previously she had been the type of methamphetamine user who did occasionally binge. She lost weight and was always agitated. She recounted the first time she met an old using friend after her recovery: “I went over to a friend’s house I had not seen for a year and a half, and I’m like, you know, I want them to see the new me, because my sponsor had showed me a picture of myself at one of the meetings on the very first time I came and I was like ‘wow.’ I wonder if I would, I wonder if everybody else would see me that different. And I ran into a girlfriend at a flea market and she said, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe that’s you. It was like your complexion, everything about you is different.’” Although her former use had taken a toll on her body, by current appearances her looks had been restored. Moreover, the infamous “meth mouth” that so many women feared had not affected Maggie. Her teeth were all her own and pearly white. Her clear complexion was smoother than was to be expected of a woman nearly fifty years old.

An explanation was needed to understand how Maggie could continue using methamphetamine and still maintain a relatively healthy body and a social life unaffected by the well-documented medical consequences of methamphetamine use and unharmed by the harsh legal repercussions that hurled many of the actively using women I interviewed into eventual abject poverty. One explanation is that she learned how to use drugs in a controlled manner, which is a harm-reduction approach that will be further explored in this book.

Maggie’s drug path is not over, and her goal is obviously complete abstinence, but unlike many women I interviewed, she appeared to be comfortable with the fact that she promoted abstinence while still using. Before Maggie left I asked her how long she thought she would she be using methamphetamine. She answered forthrightly, “Every day I wake up and I’ll say -- like what I told Julia, I’ll go with you and start over -- I’ll stop because I’ll start back at step one. I mean relapse is a part of recovery. I think I’m ready to recover.”

I had heard this from many of the women I interviewed. And knowing the current treatment options and recovery rates for methamphetamine users, I understood why she seemed facetious about relapse. Being a woman on ice was not an easy path to follow, but it was even more difficult to leave. While our knowledge of methamphetamine use and treatment is increasing, little is known regarding its use among residents living in a geographic setting that is traditionally regarded as a haven for law-abiding middle-class families -- the U.S. suburb. Yet on closer inspection, the social landscape of the suburbs is a potential breeding ground that fosters attraction to use a drug with the effects provided by methamphetamine -- energy, weight loss, and happiness.

Suburban Women

For five years I conducted ethnographic research in the suburbs of a large metropolitan area in the southeastern United States to learn more about suburban use of methamphetamine, a drug also known as ice, speed, crystal, shards, and a variety of other street names. During the last two years of the study, I focused on suburban women exclusively in order to better understand their use of this drug from their own perspectives and changes that occurred in their lives over time. The purpose of this book is to portray the everyday reality of methamphetamine use by suburban women from a diversity of social settings, social classes, race/ethnicities, and age groups. I aim to unravel what being a methamphetamine user, or addict, means to these women by examining the trajectories of their drug use within the context of suburban life.

Maggie was one of the women who seemed to navigate the world of drug users and mainstream suburban middle-class more successfully than others. Some of the women decided to leave the drug-using environment either to avoid various consequences such as loss of family or employment, adverse health effects, involvement with the criminal justice system, or as part of what seemed like a process of “maturing out” of drug use (Winick 1962). Others continued in their drug use despite serious consequences that often left them homeless, abandoned by family and friends, and facing repeated or extensive periods of incarceration. Treatment, whether coerced or voluntary, worked for some but not for others. Many women recited the sayings that I had come to recognize as the philosophy of twelve-step: “Once an addict, always an addict” or “You have to hit rock bottom first.” Yet empirical evidence shows that not all drug abusers remain addicts or recovering addicts for life, and some stop having a problem with alcohol or other drugs before they hit rock bottom (Akers 1991; Boshears, Boeri, and Harbry 2011). However, many of the women I interviewed who had relapsed multiple times repeated the twelve-step phrase I often heard -- that they needed to hit rock bottom first. Maggie was unusual in that she expressed a strong belief in the twelve-step model but did not embrace the rock-bottom mandate that was part of twelve-step lore.

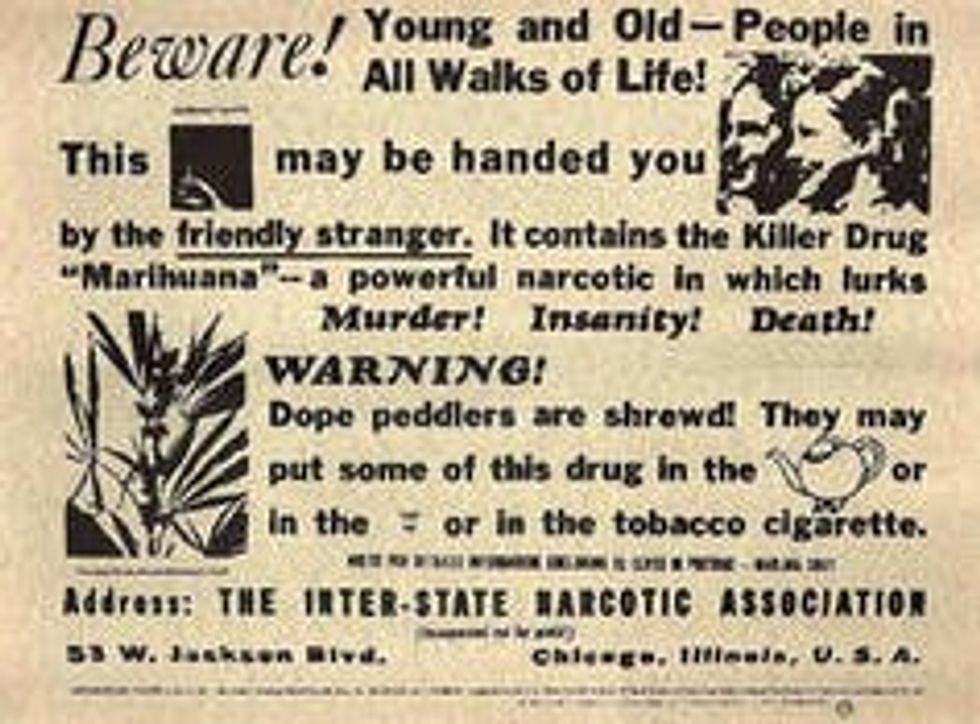

So we have to ask, what kind of people want to re-criminalize cannabis today? What are their motives? Who profits from continuing to incarcerate people for using marijuana? Whose power will be diminished when a drug that has so many health benefits is provided without a prescription?