Why you can't afford a place to live

Want to rent a place in Manhattan? Buy a house in the Sun Belt? Live virtually anywhere in the U.S.? That’ll cost you more than ever before.

It’s easy to suppose that the reason is another Wall Street movie moment where Gordon Gekko argues for the beneficence of greed. And, yes, that’s part. But the dynamics of the housing market are far more complicated and subtle. A lack of effective national housing policy combined with an easy monetary strategy turned into a major aggravating factor.

Too Much Money

Plenty of money would keep people happy, you’d think. And it does, except when it comes to money pouring into investment areas.

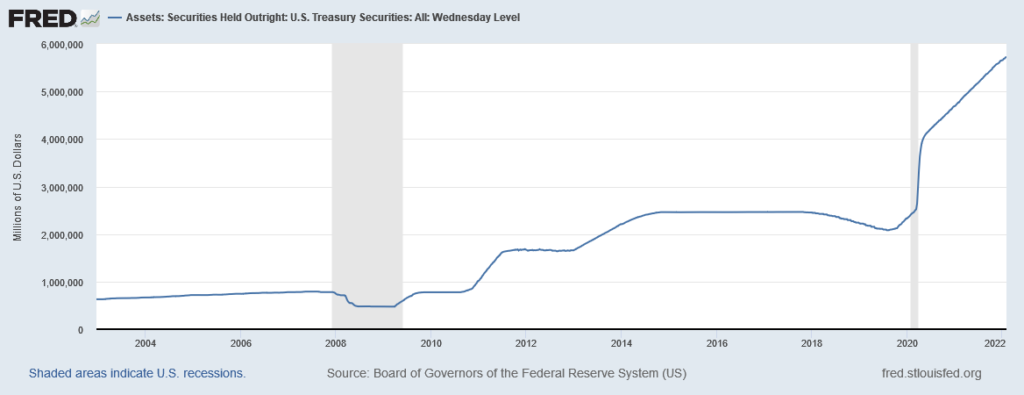

For almost 14 years, ever since the Great Recession that started in 2008, the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates historically low to encourage companies to invest and expand their businesses. The Fed also bought an enormous number of Treasury securities to keep credit markets from freezing up by injecting massive amounts of capital through these purchases. As of Feb. 2, the Fed had a total of $5.7 trillion of securities, as the graph from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis shows below.

The Fed has vastly increased its holdings of Treasury bonds and notes.

The Fed has vastly increased its holdings of Treasury bonds and notes. The institution opened the financial flood gates and left them that way for years, releasing a torrent of cash. Those selling bonds to the Fed were already typically well-off. They did what they had been taught to do, which was invest that extra money to make even more.

That started a financial feedback loop. Assets like stocks and real estate shot up in value because investors bid up the price. As the apparent values rose, more money went in to get some of that gain because low interest rates meant bonds and other so-called fixed-income vehicles didn’t pull their weight.

But with barrels of bucks floating into the real estate market, prices of properties, including apartment buildings and single-family homes being turned into rentals, kept rising.

Sky-High Construction Costs

One other part of the investment aspect is the cost of building. A sound investment means that if the owner ever needs to make improvements or, heaven forbid, rebuild after an accident, the cost would not be prohibitive. But if you think inflation is high for you, it’s much worse for construction. Prices of basic materials in December 2021 were up 13.5% over the same month in 2020, and that wasn’t counting scarcity of getting materials or labor.

When property gets more expensive, owners want to ensure they’re making enough to warrant the cost. And so, rents go up. There’s a secondary smack on the housing front. As more investors seek not just apartment buildings but houses to rent out, prices rise.

The St. Louis Fed also has data from the Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The median sales price of houses in the fourth quarter of 2021 was $408,100. Five years before at the end of 2017, that number was $337,900. It’s almost a 21% increase in five years. Most people can’t keep up with this rate.

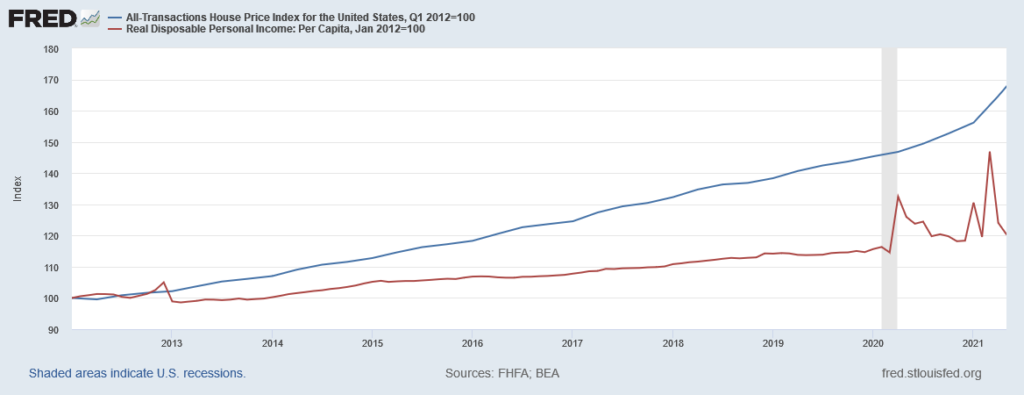

House prices (blue line) are far outpacing income.

House prices (blue line) are far outpacing income. Too Little Building

A reason investment dollars have such an impact is a lack of available housing. After the Great Recession, developers, banks and others got spooked. Property values had tumbled. Those who normally would buy land to build new homes weren’t interested in doing so until they knew prices had stabilized so the projects wouldn’t be money-losers. Lenders didn’t want to take the chance that more loans would go underwater.

The result was such a drop in building that the nation has a major shortage of houses, according to a report by real estate economics consultancy Rosen Consulting Group and the National Association of Realtors. “While the total stock of U.S. housing grew at an average annual rate of 1.7% from 1968 through 2000, the U.S. housing stock grew by an annual average rate of 1% in the last two decades, and only 0.7% in the last decade,” the report notes.

Combined with the loss of existing units through obsolescence or demolition and the gap between availability and need is 6.8 million houses.

There’s a parallel problem for apartments according to the National Multifamily Housing Council. To meet demand, the country needs “an average of 328,000 new apartments per year at a variety of price points,” and that’s happened only three times since 1989.

It’s not so much a lack of interest on the part of developers, because they are busy building housing in the Sun Belt for significant population migration from other parts of the country.

However, in older metropolis in regions land is scarce and frequently zoning regulations discourage new development because many existing residents—often those with money and political influence—don’t want more people moving into their neighborhoods.

Too Little Income

Most of the country knows this viscerally. Housing takes up an increasingly large portion of their income, as the graph below, which DCReport generated from data the St. Louis Fed collects, shows.

The graph shows indexes that represent how quickly something grows over time by comparing it with an initial value. The blue line, starting in December 2012, is growth in rents. The red line is growth in per capita income after inflation. For most people, pay doesn’t come close to keeping up, so renting an apartment or house races ahead…which most everyone who has to pay rent at the beginning of the month knows.

If you were buying a house, here’s a similar graph that shows how much faster prices grow than personal real income.

How do you get ahead if you aren’t toward the upper end of the income spectrum or lack family who can help you gather the down payment?

And greed

Developers and property owners are in this for the money, and they want to keep making more. With all the other reasons, there’s a focus on increasing house prices and rents because it’s a way to keep investments ahead of inflation. They aren’t typically focused on trying to control an important cost of living.

Governmental and Societal Inaction

In one sense, what caps it all is the lack of action on the part of governments and society. The more the nation trusts in pure market solutions, the greater a chance that things spiral out of control.

Not that smart and effective government action is easy. For instance, most rental properties are owned by smaller companies and individuals. Say that there should be a cap on rents, and you could drive those owners out of business, or at least see them give up on maintenance and repair because it becomes a losing proposition.

And yet, government could push for different zoning, offer more financing to see more housing constructed and so on. Make it easier to get people into places they rent or even own. But given the financial forces at work in politics, that doesn’t seem so likely.

- Matthew Desmond Will Change the Way You Relate to America's ... ›

- Michigan's GOP Senate majority leader has some bad news for ... ›

- Fox News' latest whopper: Only 'a very small percentage' of ... ›

- Reno seeks to purchase motels as affordable housing instead of ... ›

- 'Overvalued' Florida cities have become ground zero for 'crippling' rent hikes - Alternet.org ›