There has been an explosion of homicides in California’s county jails. Here’s Why.

Deadly violence has surged in county jails across California since the state began sending thousands of inmates to local lockups instead of prisons, the result of a dramatic criminal justice transformation that left many sheriffs ill-equipped to handle a new and dangerous population.

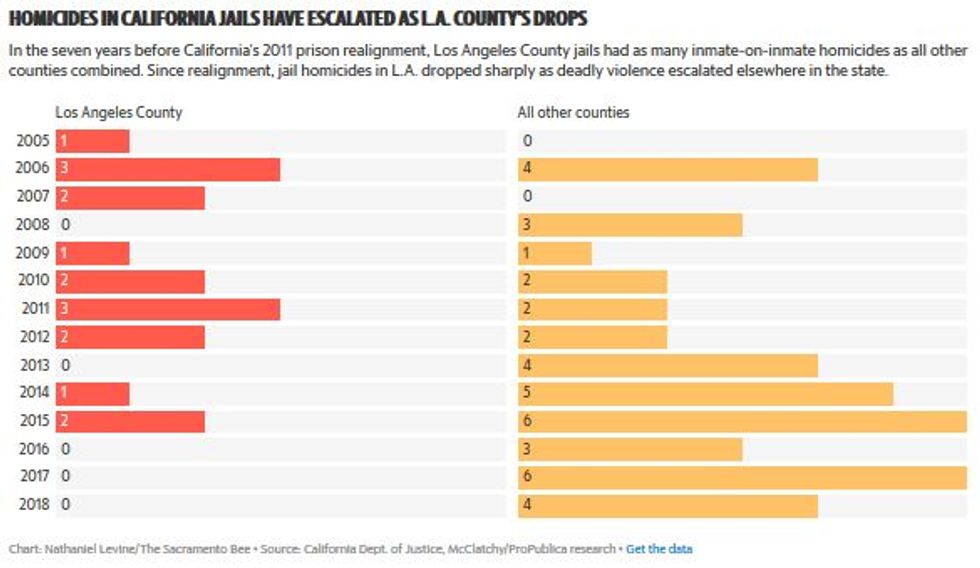

Since 2011, when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered California to overhaul its overcrowded prisons, inmate-on-inmate homicides have risen 46% in county jails statewide compared with the seven years before, a McClatchy and ProPublica analysis of California Department of Justice data and autopsy records shows.

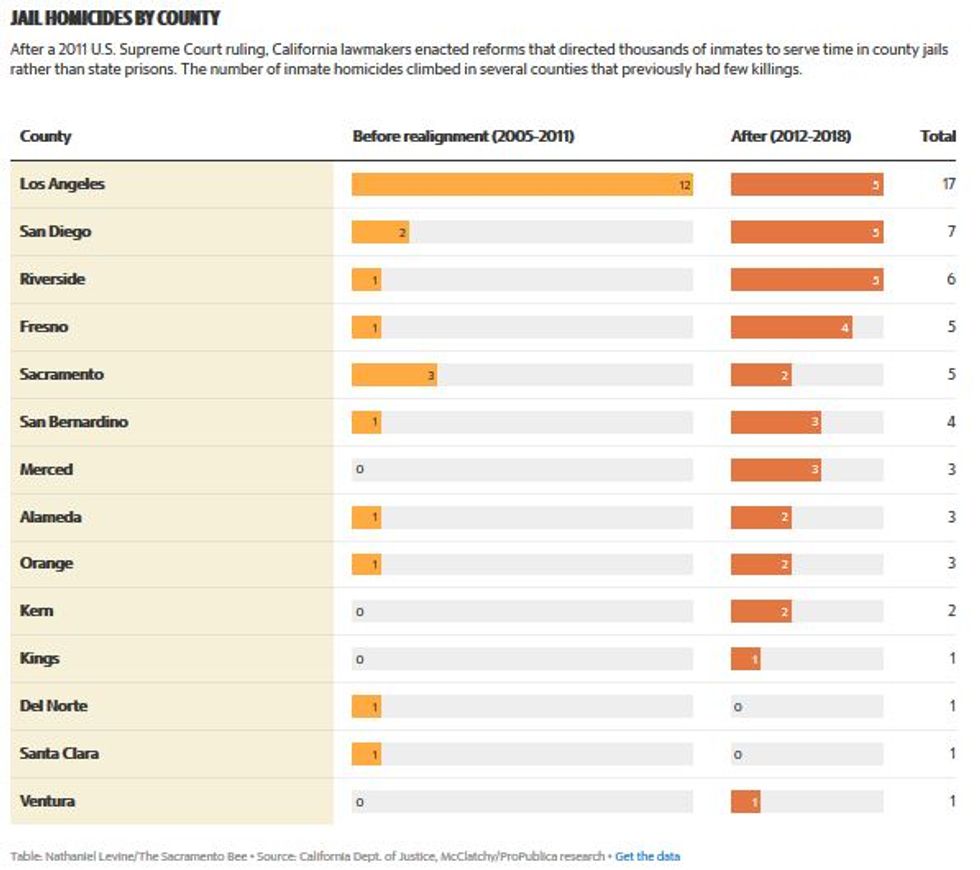

Killings tripled and even quadrupled in several counties.

The increase in violent deaths in jails began soon after California officials approved sweeping reforms called “realignment” in response to the court ruling. The result has meant the conditions in many jails now mirror those in the once-overcrowded prisons, with inmates killing each other at an increasing rate.

Inmates have stabbed, bludgeoned or strangled their cellmates, moved bodies and wiped away blood before guards noticed, autopsy reports show. Staff at the jails have missed several of the crimes entirely, only finding the bodies hours later.

The state holds more than 70,000 inmates spread across 56 counties with jails. Many inmates now are serving multiyear sentences in jails originally designed to hold people no longer than a year. An increasing number of jail inmates suffer from serious mental illness or chronic medical conditions that those facilities have been unprepared to handle.

While inmate-on-inmate homicides are up significantly in jails overall, Los Angeles County, home to more than 10 million people, including 16,000 in its jails, has been an exception. That follows a federal court order placing the nation’s largest jail system under an outside monitor in 2014 to overhaul operations after guards were caught allowing fights among inmates and other abuses. Los Angeles County jails haven’t had an inmate homicide in more than three years.

The rest of California saw its inmate homicide count soar by 150%, from 12 killings in the seven years before realignment to at least 30 in the seven years after.

The surge in killings in county jails is particularly significant because the population there is vastly different than in prisons. The majority of people in jails statewide are accused of crimes, innocent under the law, whereas prisons only hold those who have been convicted of felonies. Jails mix both populations, and the result has been deadly for some.

Three-quarters of those killed in jails since 2011 were awaiting trial, according to state data.

Some of the victims were hours away from being released.

Diverting people from overcrowded state prisons to county jails brought organized criminal activity and other new burdens to local sheriffs, said Jonathan Caudill, an associate professor of criminology at the University of Colorado who studies realignment and incarceration in California. The increase in homicides suggests jail officials lack the resources to supervise, provide services and protect the jail population, he said.

“You have the importation of prison politics into the county jail in concert with people being there longer and having to handle their problems there,” Caudill said. “It’s like fire and gasoline.”

Kill, Clean, Report

Increased deadly violence soon followed in every major California region, from the Bay Area to the Central Valley and the Southern California coastline.

In the seven years before realignment, only one jail inmate was killed in Riverside County, east of Los Angeles. But five have died in homicides in the seven years since. In San Diego County, homicides jumped from two to five in that same period.

Legislation passed to enact realignment reclassified the way the state looked at about 500 crimes to effectively eliminate the possibility of prison time. The new rules applied to anyone convicted of a crime after Oct. 1, 2011, and changed the statutes throughout California law, from the penal to the motor vehicle codes.

Realignment didn’t release people from prison early out a back door — it closed one of the front doors and made it more difficult to end up there at all.

Critics predicted the changes would inevitably lead to a spike in violent street crime statewide. But that has not happened. Researchers have found the prison realignment effort since 2011 has had little to no effect on public safety.

“Statewide violent and property crime rates are roughly where they were when California began implementing these reforms,” a Public Policy Institute of California report stated this year.

Inside California’s jails, the same has not been true. Sentenced inmates make up a greater share of the jail population statewide, and there are thousands more people held on felonies than in the years before realignment, data from the Board of State and Community Corrections shows.

The state has tried to improve conditions in its sprawling network of state prisons. But county jails — designed to hold people for weeks, not years — have long mixed low-level inmates with violent defendants in cells, including those charged with murder. But California’s in-custody death data and autopsy records indicate that risky practice has at least contributed to more deadly results in the years since realignment.

On May 8, 2013, Julio Negrete Jr. was booked into a Riverside County jail on suspicion of drug possession. Officials assigned him a cellmate accused of murder. The next day, guards went to escort Negrete, 35, to a bond meeting but couldn’t find him. They searched the cell from top to bottom, found bloody socks and then came upon his strangled body under the lower bunk hidden by two small cardboard boxes, coroner and court records state. Video footage showed the attack happened roughly 10 hours earlier.

In a written statement, the sheriff's department said it is "always troubled" by inmate violence and investigates every assault in Riverside County jails. The agency said the five homicides since 2011 are not the result of its own failings. "When looking back at the totality as a whole, the assaults were discovered to be isolated from one another and acts of opportunity rather than a lapse of policy or procedure," the department said. "All staff performed professionally and utilized their training to provide safety and security to the facility."

Ross Mirkarimi, a former San Francisco County sheriff who now reviews inmate deaths, said of county jails: “The system obviously has fundamental blind spots. Those who are hellbent on committing murder know how to defeat those blind spots.”

Mirkarimi said local sheriffs haven’t reacted with enough alarm to deaths in jail custody. He said that if dying in a cell is “the most vivid feature” of a jail’s shortcoming, a doubling of inmate-on-inmate killings should sound a blaring siren.

When dangerous or mentally ill inmates strain a short-handed staff, every part of a jail suffers the consequences. Officers are sometimes slower to conduct rounds, to see fights develop in a housing area for dozens of gang members or to notice other signs of trouble. They often arrive too late to save lives.

Boredom and frustration alone can create tension among cellmates, said Michael Bien, a lawyer representing inmates in lawsuits against California prisons and several county jails. “We know that incarcerating someone in a place where you don’t have anything to do is likely to lead to violence, mental illness, stress, suicide, all sorts of things.”

On Dec. 14, 2014, a deputy at the Sacramento County Jail was conducting overnight rounds in a pod for sick prisoners where Edward Larson was housed. Larson, 54, was a mentally ill homeless man jailed for failing to register as a sex offender.

Jail staff assigned him a new cellmate after another inmate complained of Larson’s lewd comments and poor hygiene. His behavior also bothered his new cellmate, Ernest Salmons, who alerted a deputy at 3:10 a.m. that something was wrong. Larson was lying on his back, eyes closed and a blanket pulled up to his neck.

The deputy instructed Salmons, who was in jail on suspicion of stealing a vehicle, to nudge Larson, according to the district attorney’s death-in-custody review, so Salmons jostled Larson’s mattress. He was unresponsive, his skin cool to the touch, and firefighters pronounced him dead minutes later. His autopsy report shows he was beaten to death sometime after the previous night’s “stand-up count,” when inmates must stand so guards can take attendance. After that, staff only peer through cell windows for hourly checks.

Salmons first denied fighting Larson. But investigators noticed small areas of smeared blood on the wall of the cell, which had two beds. They found a bloodied T-shirt in the trash can and remnants of pooled blood on the floor. Larson’s head was bandaged, although he had never asked for a bandage. Salmons, however, received several of them.

“It appears,” investigators wrote, “someone had tried to clean up blood from the cell.”

Salmons was convicted of the killing and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

The Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office initially agreed to an interview about the safety of its jail. Then it rescinded the offer, saying instead it would only provide written answers to questions. Then it changed course again, saying the “topics” were the subject of “ongoing litigation” and it would answer no questions.

“I can tell you that the Sheriff’s Office is aware of the concerns regarding these topics,” Sgt. Tess Deterding, a spokeswoman, wrote in a statement.

“Agitated and Shirtless”

It’s not clear why Lyle Woodward was even in the San Diego Central Jail in early December 2016. Police had arrested him for alleged drug possession weeks earlier, though county officials later claimed in a court filing that he was jailed on a parole violation. Woodward had a history of mental illness and drug cases.

Regardless, on Dec. 3, correctional officers responded to a “man-down” alert and found Woodward unresponsive, sprawled facedown on the cell floor with blood pooling around his head, according to medical examiner records. Jail staff described one of Woodward’s cellmates as “agitated and shirtless.”

Cellmate Clinton Thinn, a New Zealander charged with armed bank robbery, told officers he’d fought with Woodward several minutes earlier. However, bruises on Woodward’s neck suggested something had been tied around his throat to choke off air. In the cell toilet, officers found a jail-issued blue shirt, torn into strips and knotted together. “It is unclear if the suspect attempted to flush the shirt portion,” the autopsy report stated.

Medics rushed Woodward to a nearby emergency room, where doctors and nurses resuscitated the 30-year-old. But his brain was gravely injured, and he began having seizures. Woodward’s condition worsened; his parents told the hospital to stop life support, and he died a week after the attack.

Last year, a jury convicted Thinn of murdering Woodward and sentenced him to 25 years in prison. Woodward’s parents have filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against the sheriff’s department, alleging that jail staff failed to protect their son from a dangerous inmate and was slow to provide medical care. The sheriff has denied the allegations.

In written answers to questions from McClatchy and ProPublica, the sheriff’s department said the number of high-risk inmates inside San Diego County’s jail increased after realignment. It responded by forming a jail investigations unit.

“They work closely with facility staff members to develop, share and act upon information which could lead to violence and prevent it when possible,” Capt. Alan Kneeshaw wrote. “When assaults occur, they are documented and investigated.”

In Los Angeles County, a federal monitor and members of the public look into jail violence — not just the sheriff’s department. That independent scrutiny exists in only a couple of other California jurisdictions. And jail staff in Los Angeles didn’t volunteer for it.

Home to a quarter of the state’s residents, Los Angeles County once had as many inmate killings as the other 55 county jails combined. In 2011, as state officials negotiated prison realignment, civil lawsuits and news reports exposed that guards at Los Angeles’ Men’s Central Jail intentionally allowed inmates to assault each other.

County officials instituted an array of measures to protect people in the cells, including a civilian oversight board. The federal courts appointed an independent jail monitor.

Richard Drooyan, an attorney and the court-appointed monitor for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, said every jail fight is reviewed to ensure staff members followed safety protocols and intervened quickly. Gang members and other high-risk inmates are escorted by guards when they leave their cells to prevent violence.

In other county jails, court and autopsy records show inmates accused of serious violent crimes or suffering psychosis are sometimes housed with people facing minor charges. “That’s not the way they run the jails down here,” Drooyan said of Los Angeles County. The nation’s largest jail system now segregates and tightly controls where the high-risk inmates go and what they do, he said.

The fixes appear to have reduced violence overall and homicides in particular. State in-custody death data shows Los Angeles County had 12 inmate homicides from 2005 to 2011, compared with just five from 2012 to 2018.

An inmate has not been killed by another person in custody in more than three years.

Today, officers and administrators in the Los Angeles County jails “understand their obligations to protect the inmates and they take those obligations pretty seriously,” Drooyan said. “And I think that it’s reflected in the statistics.”

Update, June 13, 2019: This story was updated with a statement from the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department.

This article was produced in partnership with The Sacramento Bee, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

This story is part of an ongoing investigation into the crisis in California’s jails. Sign up for the Overcorrection newsletter to receive updates in this series as soon as they publish.

You spent 12 years in the Marines. When were you sent to Iraq?

You spent 12 years in the Marines. When were you sent to Iraq? You fired into six or ten kids? Were they all taken out?

You fired into six or ten kids? Were they all taken out? Losing Faith

Losing Faith