You might think the NFL is racist. An insider says he’s about to prove it in court.

Jim Trotter’s new job at NFL.com began with the former ESPN and Sports Illustrated staffer noticing there were no Black people in decision-making positions at the National Football League-backed news website and multimedia hub.

This was five years ago, and at first, Trotter complained to NFL business managers, noting that the NFL’s workforce includes nearly 60 percent Black players. When no Black people got big jobs at NFL.com, he began to complain in media appearances.

Then, finally, he confronted the top boss – NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell – at the Super Bowl.

“When are we in the newsroom going to have a Black person in senior management, and when will we have a full-time Black employee on the news desk?” Trotter asked.

In May, the NFL declined to renew Trotter's contract. In September, he filed a racial discrimination lawsuit with the Southern District of New York. The NFL has until Friday to respond in court.

The Trotter lawsuit is what happens when a man is turning 60, has borne witness to a boatload of racism and he’s grown sick of it all, tired of hearing transparent lies.

Unconsciously, fans believe sports leagues are akin to American utilities. In reality, they’re government-backed business consortiums. A utility might employ an inspector general. A business consortium absolutely will not.

Trotter is a Black journalist by trade and heart. But by joining the NFL’s media arm, did he really think the NFL was going to let him do actual journalism or work for a Black journalism executive who might have different ideas than the league’s party line on issues such as … race?

I remind Trotter that the league only just became comfortable with letting Black people play quarterback, never mind making real-world decisions. That for decades held onto the name “Redskins” as though it were a family heirloom. This is the NFL, I don’t have to remind him, that ignored a concussion crisis at the center of his book on now-deceased linebacker Junior Seau, then relied on a wild racist theory in search of lawsuit settlement savings. This is a league filled with white team owners who in word and deed keep revealing themselves as people who believe Black people are lesser people.

ALSO READ: A deafening silence from Sen. Tommy Tuberville’s Black football players

“They’re all racists,” I tell Trotter with great confidence. If they aren’t racists, they’re magnificent accessories.

“I don’t believe that every owner is racist,” Trotter replied.

“Oh okay.”

“I know owners that I don’t believe to be racist. I know them personally,” Trotter insisted.

So really really, I ask the current National Association of Black Journalists’ journalist of the year: What did you think would happen by working for the NFL? Did you think you could change the culture by revealing how racist a racist league is? I mean, reporting on racism inside the NFL is like exposing the monosodium glutamate inside Doritos. Frito-Lay ain’t havin’ that.

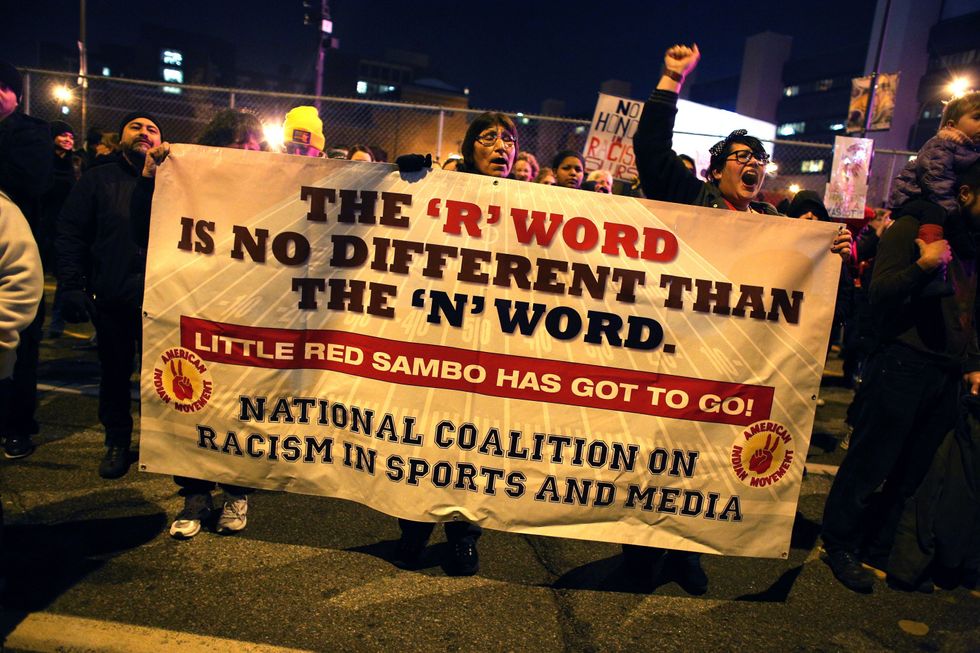

Native Americans protest before the Minnesota Vikings and Washington Redskins game on November 7, 2013, at Mall of America Field at the Hubert Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis, Minn. The team is now known as the Washington Commanders. Adam Bettcher/Getty Images

Native Americans protest before the Minnesota Vikings and Washington Redskins game on November 7, 2013, at Mall of America Field at the Hubert Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis, Minn. The team is now known as the Washington Commanders. Adam Bettcher/Getty Images

But Trotter’s plans are even more ambitious now, he explains.

“It’s not enough to say you know these things,” Trotter says. “It’s like the old Training Day line: It’s not what you know, it’s what you can prove.”

Even a cursory look at his complaint against the NFL suggests Trotter can prove a lot.

Jim Trotter isn’t constrained to seeing the NFL as a bastion of old-school male militarism that preserves outmoded problem solving, a troublesome addiction. Bless his heart.

“History has taught us that there are only two ways that we see substantive change in the NFL,” Trotter said. “One is through the threat of litigation or actual litigation, as we saw in the early 2000s with Johnnie Cochran and Cyrus Mehri, [when they] threatened to sue the NFL for discriminatory [coaches] hiring practices. And all of a sudden the league implemented the Rooney Rule and you saw the number of Black head coaches increase.

“The other way we’ve seen substantive change is through the threat of lost revenue by sponsors. When FedEx and others threatened to pull out of their sponsorship agreements with the Washington Commanders we saw the league and the owners get Daniel Snyder up out of there because it was bad for business,” Trotter said.

Trotter says that in 2021, a reporter on a call with 40 other staffers said that he heard Bills owner Terry Pegula say, “If Blacks think it’s so bad they should go back to Africa and see how bad it really is.”

The news went unremarked upon, and at the meeting’s end, according to Trotter, he asked, “Are we not going to address what we heard here?”

Management said they would get on it, he said, and nothing happened.

Later that year, then-Oakland Raiders Coach John Gruden was found to have said of Players Association chief DeMaurice Smith in an email: “Dumboriss Smith has lips the size of Michelin tires.”

Trotter went on TV and called Gruden’s exposed insult “just a tree in a forest of NFL racism.”

ALSO READ: National Football League sins: a one-man tribunal to judge them

Trotter also planned to go public with a statement by Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones — “If Blacks feel some kind of way, they should buy their own team and hire who they want to hire” — and was talked out of it by bosses. After all, this is the owner who said any player who pulled a Kaepernick, and kneeled during the National Anthem, would be fired. Seemed apt.

Early this year, Trotter says his supervisor told him they could see no reason why his contract wouldn’t be renewed in the spring.

But the Gruden and Jones episodes, coupled with his keeping quiet about the NFL asking players to begin warming up after Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin nearly died in a game against the Cincinnati Bengals — the league ultimately canceled the game — took Trotter through the looking glass.

As he explained to journalist Jason Jones, “That was the point, really, Jason, that I was like, I can’t take this anymore. I can’t sit by and go along to get along and accept it.”

The lawsuit showcases problems inherent to covering any employer from within:

“It would be like if you were a political reporter and a member of Congress is paying your salary. There’s just an inherent conflict,” says Aaron Chimbel, dean of the Jandoli School of Communication at St. Bonaventure University. “That’s sort of the whole idea of a free press and the fourth estate: You have people who are disconnected from who they are covering and what they are covering.

“That doesn’t mean you don’t do good work and can’t make efforts to provide important information,” Chimbel continued. “It’s just really hard for anybody in that circumstance to have the freedom that you would be if you were working for an independent news organization. I think you know when you’re employed by a team or an organization that there are inherent boundaries to what you’re being allowed to report on.”

Trotter said that he had been assured upon accepting the NFL.com position he would be allowed to report news involving sensitive issues with owners. Opining on the issues would be off the table at NFL.com, but reportage was valued.

“What I didn’t understand – and you can call it my naivete if you want,” Trotter said, “is that what he meant by that is, ‘We will always report the news if everyone else knows about it. But when we become privy to sensitive things, such as comments by Jerry Jones or the alleged comment by Terry Pegula and no one else knows about it, then we won’t report it.’”

The Trotter case has most often been framed by two press conference responses to Trotter questions, both by NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell.

At the first press conference, prior to last year’s Super Bowl, he appeared to catch Goodell off-guard before the hot lights, cameras and world press.

“Why does the NFL and its owners have such a difficult time at the highest levels hiring Black people into decision-making positions?” Trotter asked.

Goodell stammered:, “If I had the answer right now, I would give it to you. I think what we have to do is just continue and find and look and step back and say, ‘We’re not doing a good enough job here and we are the ones who have to make sure we bring diversity deeper into our NFL and make the NFL an inclusive and diverse organization’.”

When Trotter saw no change in his workplace conditions, he queried Goodell again. This time, it was at the press conference before February’s Super Bowl at SoFi Stadium, up the road from his San Diego home. He introduced himself as Jim Trotter from NFL.com.

“I asked you about these things last year and what you told me is that the league had fallen short and you were going to review all of your policies and practices to try and improve this.”

Black sports fans all over the nation muttered to themselves, Welp, that Negro’s getting fired.

When you listen to the audio, there’s a certain exhaustion inTrotter’s voice that’s as tired as his question itself. (Ain’t no tired like old Black journalist-tired.) It’s important to note the exhaustion, because Trotter is a sports journalism success story, a guy who’s pulled himself up through the ranks — nine years covering the Chargers for the San Diego Union Tribune, an old pro who can smell a lie a mile away.

Before reading the substance of the commissioner’s response, know that Roger Goodell is no CTE-addled ex-player. He’s a polished PR specialist who worked his way to owners’ Top Employee status by navigating them through numerous public crises.

To introduce his comments, Goodell un-narrowed his eyes, denied being “in charge of the newsroom,” and said this:

“We did go back and we have reviewed everything we’re doing across the league. And I do not know specifically about the media business – will check in again with our people – but I am comfortable that we made significantly (sic) progress across the league. That includes in the media room. Those are things we continue to look at and hopefully make real progress to. I can’t answer, because I do not know, specifically what those numbers are today.”

So, not-racist Roger Goodell hadn’t just opted out on repairing the racist exclusions of his company’s media arm, he’d also not even taken Trotter’s born-of-desperation, public-as-possible 2022 question seriously enough to prepare a competent response.

“And yet, a year later nothing has changed," Trotter said. “When are we in the newsroom going to have a Black person in senior management, and when will we have a full-time Black employee on the news desk?”

Even PR will people tell you who they are, if you let them, and Occam’s Razor very much applies here.

Not only has my emailed interview request to the NFL commissioner’s office gone ignored, the NFL Players’ Association, too, has declined to comment on Trotter’s diversity fight.

Trotter’s former ESPN colleague, Stephen A. Smith – who called Trotter foolish on his podcast – asked Goodell about the case on-air. But when Trotter texted Smith afterward to ask why Smith’s questions, in his opinion, were so poorly informed, Smith sent an angry and caps-laden, exclamation-filled response, Trotter said. (ESPN said Smith would not be talking to me about the matter.)

“If you watch Stephen A,” Trotter told me, “you can see that his approach is different with players – with Black men in particular – versus what it is with powerful white owners and powerful commissioners.”

“You have to understand the landscape,” he continued. “The NFL has a lot of media partners and the NFL has a lot of power and reach. The people in charge, many of whom do not look like me, are going to be more sensitive in how they cover this and what they say. I’m not surprised at all that to this point the coverage has not been extensive.

“I can remember instances at ESPN where I would say something (on air) and get a text message from my supervisor, saying that I had crossed the line,” Trotter recalled. “And I was like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. Really?’”

Trotter’s focus on meaningful change is especially critical, as, across the sports media landscape, diversity numbers increasingly get juiced by former athletes on camera rather than actual journalists who probe — often in uncomfortable ways — uncomfortable truths about the business of sports.

As Trotter reminded me last weekend, a significant lot of these on-air ex-athletes have their questions prepared by managers.

Today, Trotter is employed as an opinion writer at The New York Times-owned The Athletic. He’s won the NFL’s Bill Nunn Award – which comes with membership in the Pro Football Hall of Fame – and the National Association of Black Journalists’ Journalist of the Year prize. He’s going to be just fine.

But most Black football fans don’t think about equity or who truly profits from the inestimable cash cow that is the National Football League. Give us a pre-game Air Force flyover, a dope Super Bowl halftime show and a last-second victory and we’ll shut up. At least our people get to call plays on the field.

But as Jalen Rose – newly unshackled from his ESPN chains after he was laid off – told his Instagram followers earlier this month, the disparities between the Black American-dominated sports leagues remain striking: Dress codes and a salary cap for the NBA, the inability of their athletes to go professional after high school, as in golf, tennis. baseball or hockey.

As anyone who’s seen a Georgia congressional map will tell you, controlling Black power remains central to the American experiment. This is why Jim Trotter’s NFL discrimination suit, despite its doe-eyed, Don Quixote quality, is critical.

Without transparency for the league’s inner workings, and actual change in how those inner workings work, a plantation mentality will remain the league’s go-to trick play that maintains the status-quo and keeps Black people down.

Donnell Alexander is a freelance writer based in California. His West Coast Sojourn Substack newsletter covers the heights of his nation’s sports and culture each Monday.

- A formerly prominent gay marriage opponent is now going all-in on anti-mask outrage ›

- A brilliant video skewers Ivanka Trump by contrasting her flowery speech with the brutal reality under her father ›

- Watch: Kari Lake threatens to cancel the Super Bowl if the NFL objects to her immigration policies ›

- 'Insult to our intelligence': Columnist rips sportscaster’s defense of Cowboys owner Jerry Jones’ 'racist' remarks ›

- 'Go back to the projects': Alabama football fans shout racial slurs at Texas players ›

- Minnesota Vikings player Alexander Mattison shares racist ... ›

- The N.F.L.'s Race Problem - The New York Times ›

- Former Dolphins head coach Brian Flores sues NFL, three teams ... ›

- The NFL is a billion dollar 'plantation' | Cognoscenti ›

- The NFL's Racist 'Race Norming' Is an Afterlife of Slavery | Scientific ... ›

Then-Auburn head coach Tommy Tuberville watches from the sidelines during the final minutes of the Tigers 37-15 loss to Georgia on Nov. 11, 2006, at Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn, Alabama. Kevin C. Cox/WireImage/Getty Images

Then-Auburn head coach Tommy Tuberville watches from the sidelines during the final minutes of the Tigers 37-15 loss to Georgia on Nov. 11, 2006, at Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn, Alabama. Kevin C. Cox/WireImage/Getty Images