Since Kirk’s death last week, a number of his followers from the Christian right have ascribed him the title of “martyr”. President Donald Trump himself called Kirk a “martyr for truth and freedom”.

Similarly, Rob McCoy, a pastor emeritus from California, said at a Sunday morning church service

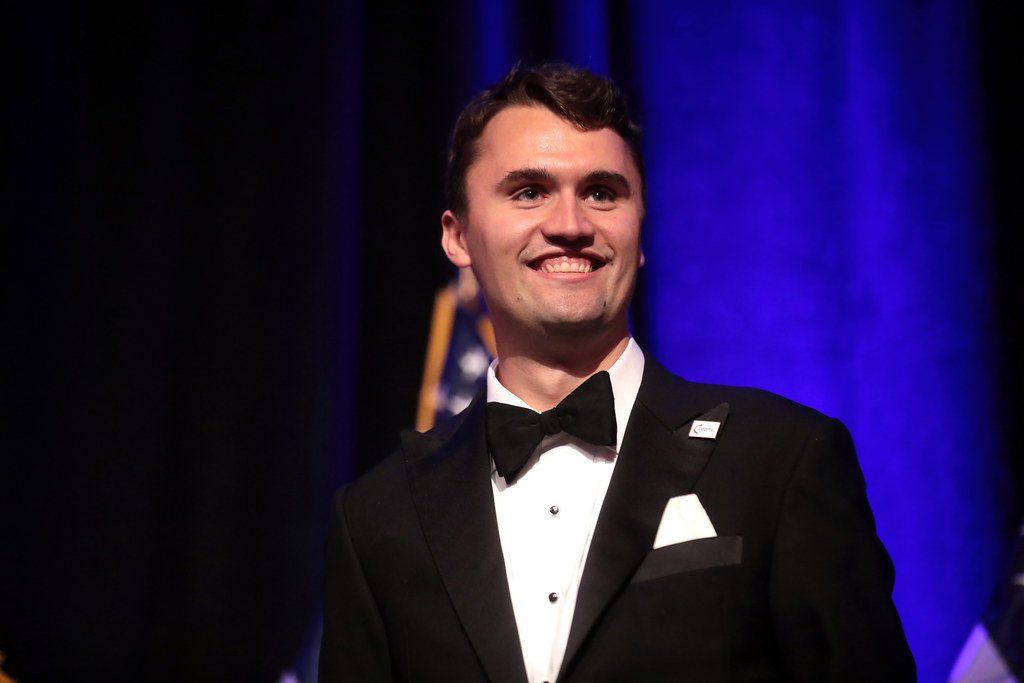

Today, we celebrate the life of Charlie Kirk, a 31-year-old God-fearing Christian man, a husband, father of two, a patriot, a civil rights activist, and now a Christian martyr.

Looking back at the history of martyrdom offers insight into what it means for Kirk to be hailed a martyr, both for his memory, and for the future of the United States.

From witness to criminal to witness again

The term martyr emerged in ancient law courts with the Greek word martus, meaning a witness or person who gives testimony.

From their earliest days, Christians appropriated it to refer to those who testified to the gospel of Jesus Christ. The gospel of Luke even concludes with Jesus telling his disciples: “You are witnesses – martyres – of these things” (Luke 24:48).

Early Christians regularly ran afoul of Roman authorities, and were brought to court as criminals. The charges generally revolved around questionable loyalty to the Roman state and religion. Could someone worship Jesus and also offer sacrifice to the traditional gods, including the emperor or his divine spirit (his “genius”)?

Christians and Romans alike thought not. From the 2nd century onward, accounts of these trials centred on a single question: “are you a Christian?”. If the answer was “yes”, execution followed.

For local authorities, the executed person was a criminal. But for fellow Christians, they were witnesses to the truth of the gospel, and their deaths were evidence of the Christian God. They were both witness and testimony – “martyrs” in every sense.

In 2004, scholar of early Christianity, Elizabeth Castelli, argued martyrs are born only after their death. The martyr isn’t a fact, but a figure produced by the stories told about them, and the honour afforded them in ritual commemorations. A person isn’t a martyr until other people within a specific community decide they are.

To understand what makes someone a martyr, we have to ask two questions:

- what are they a witness to? As in, what ideal or cause led to their death and how did their death testify to it?

- who are they a witness for? Who tells their story and who calls them a martyr?

Boundaries and borderline cases

The history of martyrdom is also a history of debates over what kind of death “counts”, and what role martyrs play in the church.

Questionable cases have accumulated through the decades. Some “martyrs” volunteered eagerly, perhaps too eagerly.

On April 29 304 CE, an archdeacon named Euplus stood outside the city council chamber in Catania, Sicily, shouting: “I want to die; I am a Christian”. After some discussion, the governor sentenced him to torture and he died of his injuries. Was this martyrdom, or suicide?

Under Christian emperors from the 4th century on, soldiers who died fighting Persians (or later Arabs) also came to be called martyrs. A soldier’s death is especially considered martyrdom if they fought against members of a different religion.

However, the soldier-martyr label has also raised anxieties. The most recent example came from the troubling claim by Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kyrill that Russian soldiers who die fighting in Ukraine are martyrs – despite fighting fellow Orthodox Christians. What do these soldiers testify to?

The stories of martyrs define community borders. Those who kill martyrs tend to be treated as enemies of the faith, whether they are Roman authorities, enemy combatants, or even people assumed to be complicit in the event.

The MAGA martyr

Let’s apply the two questions above to Charlie Kirk, who has been dubbed both “martyr” and “patron saint of MAGA”.

What would Kirk be a martyr to? To his supporters and those on the MAGA right, he died for free speech, for Judeo-Christian values, for a commitment to “Western civilisation”, and supposedly for the “truth” itself.

To others, especially those he attacked and denigrated publicly – such as queer and trans people, immigrants, Muslims and feminists – he died for white nationalism, hatred and exclusion.

This takes us back to the second question: who is Charlie Kirk a martyr for? Clearly, the answer to this is Christian nationalists, MAGA supporters and the broader American right.

He testified in life to their shared beliefs and values, and in death is their “patron saint”. The legacy of Kirk’s death will be to define who is part of this community, and who is excluded. The question then is, will a division framed in such polarising terms come to define American society as a whole?

From revenge to love

Following Kirk’s death, people on the far-right called for violent revenge against the left – even though the shooting suspect’s political motivations are unknown.

Media have reported a surge in radicalisation on right-wing platforms. There was even a website, now removed, dedicated to doxxing anyone who spoke negatively about Kirk and using that information to get them fired.

Against this rhetoric of revenge, the history of martyrdom offers a different way forward. The early theologian, Clement of Alexandria, said someone becomes a martyr not because of their death, but because of their love.

The only true witness, he argued, is love, because God is love. The only honour one can offer the martyrs is to love as they loved. Clement suggests it’s possible to reject vengeance and sectarianism, even if one loves the martyrs.

Jonathan L. Zecher, Associate Professor, Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.