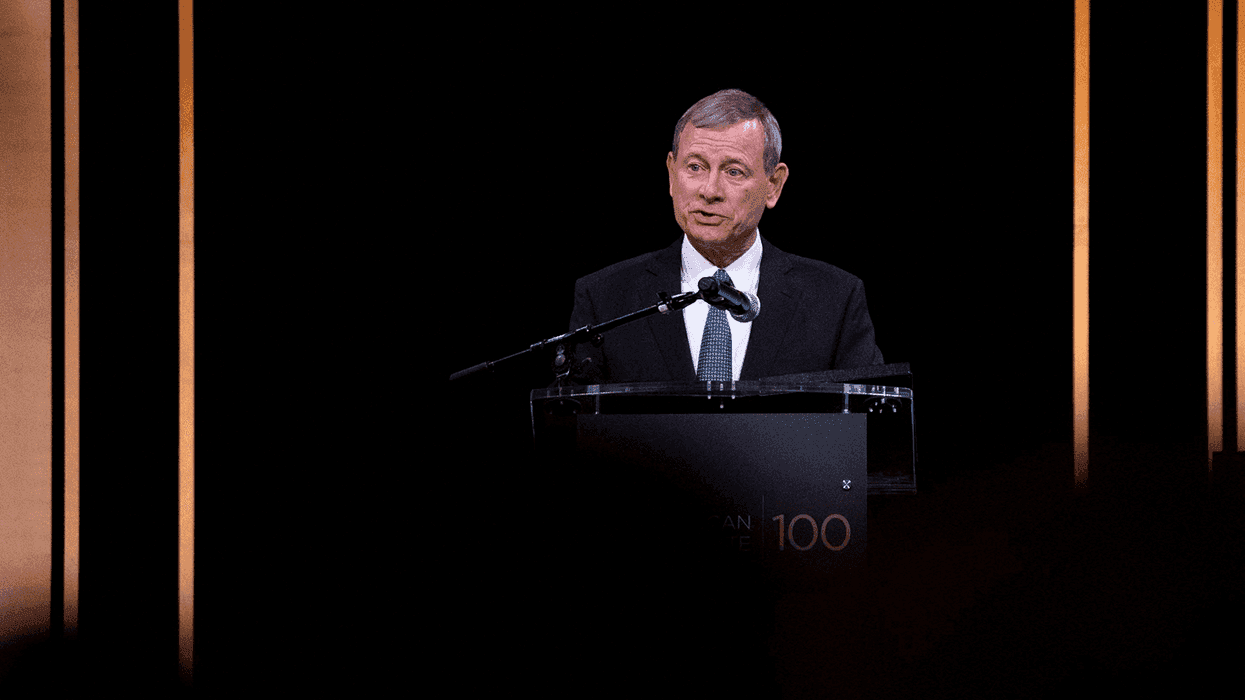

FILE PHOTO: U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts in Washington, D.C., May 23, 2023. REUTERS/Sarah Silbiger/File Photo

Although Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the United States' last nine presidential elections, they have had terrible luck with the U.S. Supreme Court — which has had a hard-right GOP-appointed 6-3 supermajority since 2020. And the High Court's image, according to Gallup, has suffered a great deal: in Gallup polls conducted in 2025, approval of SCOTUS ranged from 39 percent to 42 percent.

In an article published on February 2, the New York Times' Jodi Kantor stresses that the Supreme Court has grown increasingly "secretive" as its approval remains historically low.

"In November of 2024, two weeks after voters returned President Donald Trump to office, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. summoned employees of the U.S. Supreme Court for an unusual announcement," Kantor explains. "Facing them in a grand conference room beneath ornate chandeliers, he requested they each sign a nondisclosure agreement promising to keep the Court's inner workings secret…. Trust in the institution was languishing at a historic low. Debate was intensifying over whether the black box institution should be more transparent. Instead, the chief justice tightened the Court's hold on information."

Kantor continues, "Its employees have long been expected to stay silent about what they witness behind the scenes. But starting that autumn, in a move that has not been previously reported, the chief justice converted what was once a norm into a formal contract, according to five people familiar with the shift."

New York Times sources who described the nondisclosure agreement, according to Kantor, did so on condition of anonymity.

Kantor reports, "Former clerks and academics, told by The Times about the Supreme Court's new nondisclosure agreements, said they were a sign that the justices felt they could no longer rely on more informal pledges or longstanding norms to guard their internal workings from public view."

Jeffrey L. Fisher, a former clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens who is now with the Stanford Law School, told the Times, "They feel under the microscope and are unwilling to rely simply on trust."

University of Florida law professor Mark Fenster described the contracts as "a sign of the Court's own weakness."

Read Jodi Kantor's full New York Times article at this link (subscription required).