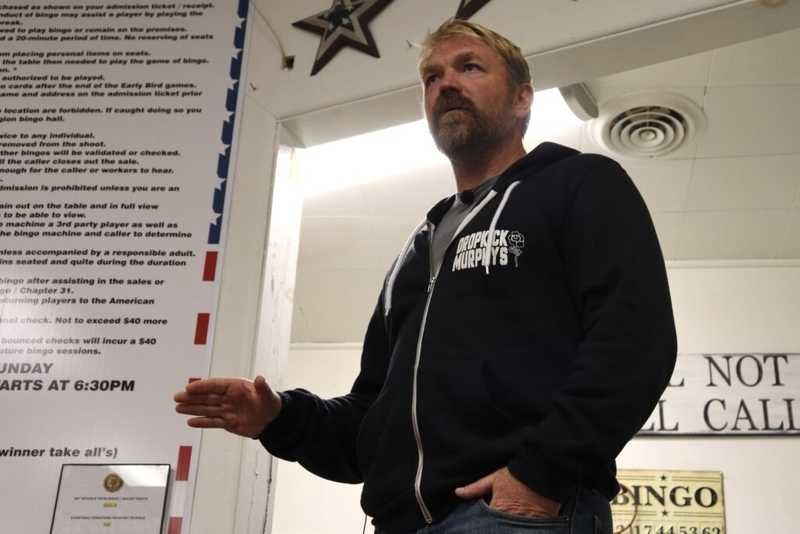

Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate Graham Platner speaks to a crowd of about 200 in Caribou on Oct. 4, 2025. (Photo by Emma Davis/ Maine Morning Star)

When it comes to Graham Platner, I don’t have skin in the game. I live in Connecticut, not Maine. The good people of that state will figure out for themselves whether he has the right stuff to be their next Democratic candidate for the US Senate. Indeed, there’s a lot to sort through, including the story of his Nazi tattoo. I wish them the best.

My interest in him is personal, not political. Platner claims to be the son of the American working class. On the basis of that authority, he hopes Mainers will give him the power to fight for the common man against an oligarchy that’s crushing him. “I’m a veteran, oysterman and working-class Mainer who’s seen this state become unlivable for working people,” he has said. “And that makes me deeply angry.”

But Graham Platner is not the son of the American working class. This is evidenced by a few facts about the world he was born into. His mom is a restaurateur. His dad is an attorney and elected official. His dad’s dad was a famous architect and furniture designer. Warren Platner was part of the firm that designed Dulles Airport and Ezra Stiles College at Yale. There’s even a chair named after him, the Platner Armchair.

That Graham Platner is not the son of the American working class is also evidenced by a few facts about his life. In childhood, he was at one point enrolled at the Hotchkiss School, the elite prep school here in Connecticut. (He does not appear to have been there long, though.) In adulthood, after returning from military service, the oyster farm he now owns was given to him by a family friend. It was then financed in part by family money. His mom’s business buys most of his harvest.

There are many ways of interpreting these facts. To me, they paint a picture of a man born into a comfortable and supportive middle class family who over time chose for himself a “working-class lifestyle.” Graham Platner didn’t finish college. He served in the armed forces. Oyster farming looks tough. These are choices that he made amid an abundance of them. No son of the working class has such luxury.

It’s hardly damning. As I said last time I wrote about Platner, there’s nothing saying that “a decent man of integrity from a respectable bourgeois background cannot be a champion of the masses. Solidarity against the ruling oligarchy does not require warriors for the working class to be of the working class. After all, Franklin Roosevelt wasn’t.”

But since there’s nothing wrong with it, why doesn’t Platner come clean? In his most recent federal disclosure filing, which was overdue, he offered strikingly few details about his finances. Why? The answer is that there’s something more authentic about being seen as a “working-class Mainer” than in being seen as the privileged son of a well-off family who seems to have failed to live up to expectations.

More importantly, however, is this: The authenticity that comes from appropriating the culture of the working class seems to satisfy the needs of elites outside the Democratic Party who seek to reshape it.

As The Guardian’s Moira Donegan said, in Platner, “some pundits and members of the consultant class seem to have found a vehicle for their own project for the party’s reform, one that is less about policy outcomes than about transforming the Democratic Party’s image to embrace men, masculinity and a vision of a rugged, rural whiteness.”

So the problem isn’t only that Platner is a man born of good fortune who has successfully co-opted the image of the working-class man. It’s also that this image is being exploited by elites who want to move the Democrats away from being a party of multiracial pluralism to one that serves the interest of the only Americans who are supposed to count.

The belief is that in order to win again, the Democrats must relearn “a style of masculinity,” as Donegan put it, that will bring young white men back. To succeed, you must accept his “ruggedness” at face value.

When you know something about his origins, however, the truth is revealed. What kind of “masculinity” arises from the fact that his business was given to him by a family friend and that his mom, by being his best customer, effectively gives him a regular allowance?

Answer: “masculinity” as imagined by men who can afford to cosplay “manliness” without the risk and responsibility of serious manhood.

One more thing about those elites. They include more than the rich consultants who keep getting richer by advising Democrats to restore “rugged, rural whiteness” to the center of their party’s attention.

They also include what some call the pod bros or the dirtbag left. These are online personalities. Some are former party insiders. Some are self-proclaimed democratic socialists. All stand in dedicated opposition to the Democratic establishment while claiming to be tribunes of the people. They are educated, articulate, witty and ideological. They see themselves as champions of the working class.

Like Platner, none comes from the working class.

Because of that, they can’t see that he doesn’t either. All they see is his “working-class image.” He’s a “gravel-voiced vet.” He’s a “rugged oyster farmer.” In fact, Platner is a leftist intellectual’s idea of a working class man, or rather, the idea of a working-class man that’s envisioned by children of affluence who turned to leftist politics as some kind of recompense, or who see in him something that’s lacking in themselves. They want it so much they’re willing to overlook his Nazi tattoo. It’s not an indicator of questionable morality. It’s a mark of authenticity!

That Platner doesn’t carry the burdens of the working class can also be seen in the frictionless way he interacts with online leftists who will also never face the consequences of failure. They read the same books. They cite the same authors. They know the same cultural references. They share what you might call the unspoken vocabulary of the upper middle class, in which humor is usually expressed ironically – “I am not a secret Nazi,” Platner said – while conflict is expressed performatively – “Nothing p----- me off more than getting a fundraising text from Democrats talking about how they're fighting fascism,” he said.

The late comedian Paul Mooney once said that everybody wants to be Black but no one wants to be Black. Everybody desires the social capital of blackness, but no one desires the burden of racism. People take what they want – Black music, Black fashion, Black food – and leave the rest. They appropriate the product of the struggle without the struggling, which allows them to pretend to be what they’re not.

Setting aside the serious and obvious differences, I see a similar dynamic at work in Graham Platner. He wants the authority that comes with being seen as a son of the working class who has had to fight his way through life, but none of the pain of fighting. He wants to accuse his opponents of lacking the courage to do what needs to be done. And he wants influential people, the online left, to play along with him. “Nothing p----- me off more,” he said, as if he would know.

I said at the top that my interest in Platner is personal, not political. This is why. He has no idea what the struggle is. I’m sure he has had his own, but the struggle he wants Mainers to believe is his is not his. No true son of the working class can pretend like that. He knows that if he fails, he fails downward. (And if he gets a second chance, he’s lucky.) There is no time for such childish make-believe. He can’t afford it.

From Your Site Articles